Preserving Today: The State Archives’ Quest to Collect Contemporary History

Since the name of our agency is the State Historical Society of North Dakota, I’m sure many people believe we are only interested in “old” things. But that’s not true. We are just as committed to preserving today, and even tomorrow, especially in this digital age.

The North Dakota State Archives has a vast and robust 2D collection stretching from the Dakota Territory days of the 1860s, ’70s, and ’80s into the mid-20th century. Now, in addition to those eras, we are on a mission to gather and preserve materials from the 1970s to the present. These materials might not feel historic, but they are crucial to sharing the story of North Dakota and capturing everyday lives here for future generations.

While visiting my parents recently, I pulled out hundreds, maybe thousands, of photographs my mother had taken of me and my siblings while we were growing up in the 1980s, ’90s, and early 2000s. As I flipped through the many memories, I began to feel the same awe I experience when looking at similarly themed photos in the State Archives collections. Both sets of photos showed people dressed in their Sunday best, dolled up for dances, attending community events, standing with their siblings, and students in desks at school. I decided to gather some of these everyday photos of my family to donate to the State Archives so that people in 60, 80, or 100 years can experience the same awe.

Everyday photos from yesterday? You may wonder why these would be important to the State Archives. But we make it our mission to preserve and share stories from all North Dakotans from all time periods. Just because something is recent doesn’t mean we shouldn’t save it. We, as a society, must commit to preserving the now to ensure future generations will understand the past and see themselves in history.

So what kinds of materials are we looking for? Photos, videos, posters, programs, yearbooks, letters, diaries, screenshots of instant messages, emails, social media—anything that documents the life of North Dakotans. Below are a few of the categories we are particularly keen to collect.

1. Family moments: These could be holidays, birthdays, family portraits, and special moments. They capture cultural traditions, relationships, and celebrations through the decades.

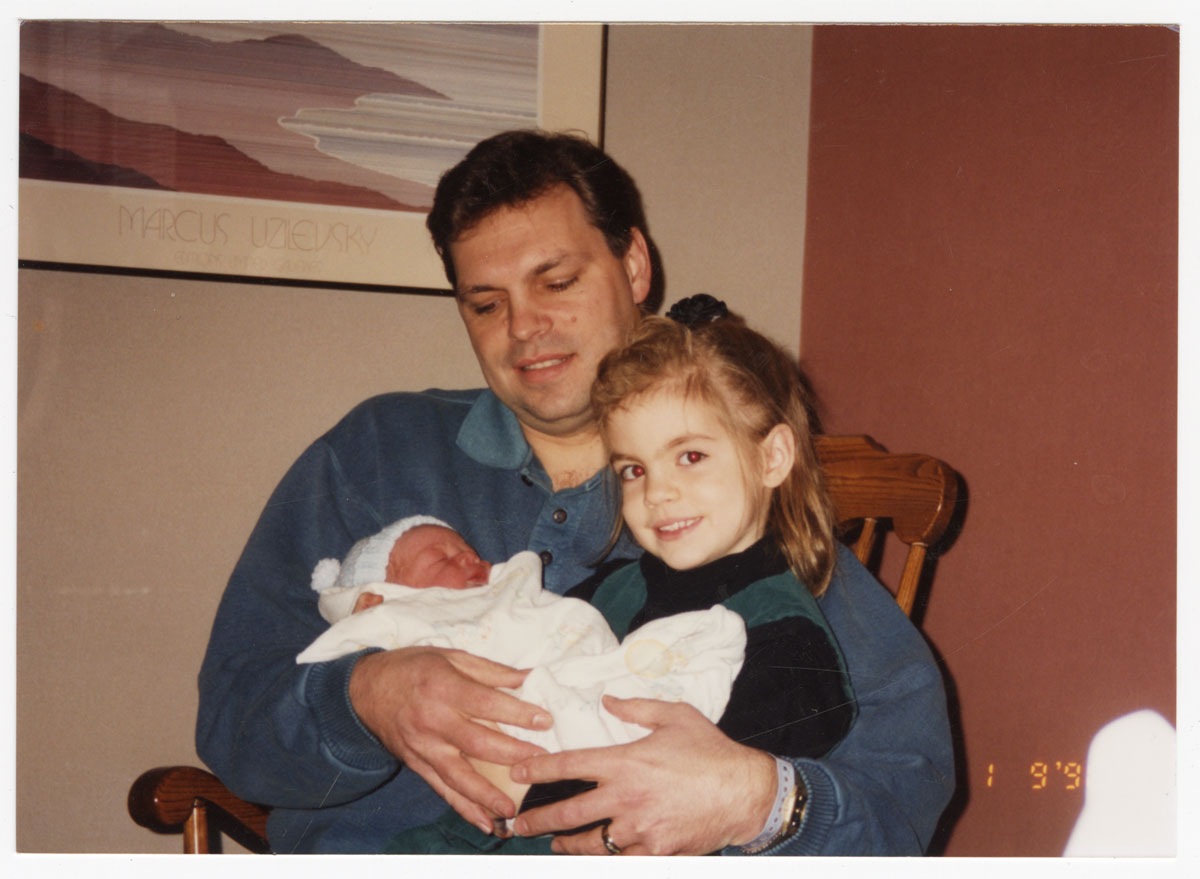

The author with her father welcomes her new baby brother in 1996. This photo offers a glimpse into 1990s fashion, newborn care, and the hospital room design of the decade. SHSND MSS 11674-00059

2. Sporting events: Whether youth leagues, high school championships, or amateur events, sports photos show what we played, how we played, and the stylish uniforms we wore.

IMCA Stock Cars lined up for the feature race at the 2024 Dakota Classic Modified Tour in Mandan. This photo captures what North Dakotans did for fun in 2024 and offers future researchers a look at car styles, paint schemes, and local culture. SHSND MSS 11674-00103

3. Daily life: These are time capsules of everyday experiences, showing the clothing, furniture, and social interactions of the era.

The author’s mom and brother enjoy an evening bike ride in 1987. Photos like this help us study 1980s house styles, landscaping trends, light fixtures, window designs, and, of course, everyday fashion. SHSND MSS 11674-00071

4. Community events, organizations, and businesses: These could include parades, festivals, church picnics, 4-H meetings, civic clubs, even street views and business fronts. They represent the spirit and values of our towns and neighborhoods.

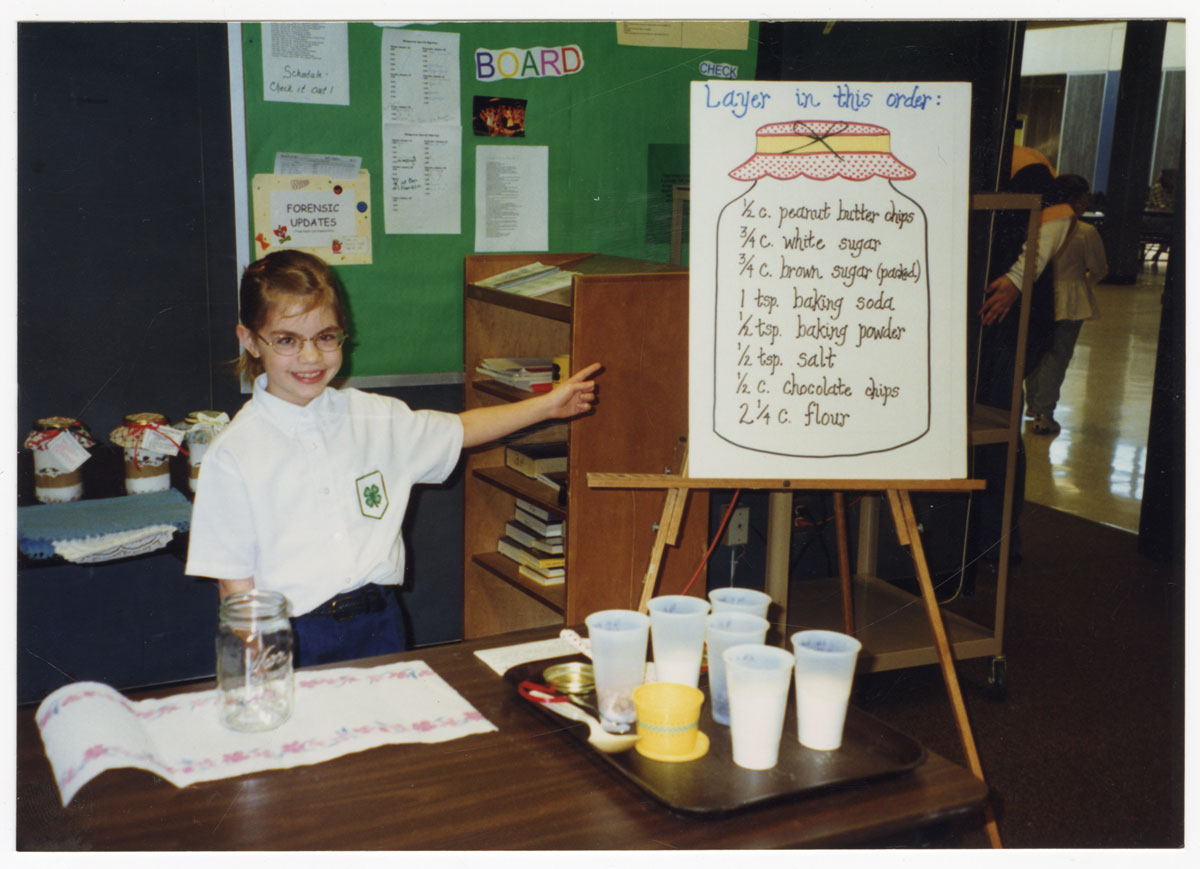

The author poses with her 4-H demonstration “Cookie Dough To Go.” This photo offers a glimpse into early 2000s youth programs, showcasing 4-H activities, uniforms, classroom setup, and cookie recipes of the time. SHSND MSS 11674-00004

5. Personal perspectives on major events: These are newsworthy happenings as seen through your lens. What did it feel like at the time? How was it experienced locally? Such materials personalize and deepen our connections to history.

A family sandbags their home during the 1997 Red River flood in Fargo. This photo shows more than just flood mitigation—it documents how families came together in a time of crisis and provides a snapshot of neighborhood layout, vehicles, clothing, and daily life in 1997. SHSND MSS 11674-00069

One day, people will want to know what volleyball looked like in 2007, how North Dakotans protected homes from floods in 1997, or what families did for fun in 1987. What we experience and participate in today is important to document. Take a look through your family photos (both print and digital) to enjoy the nostalgia and see today’s history. For more information on donating to the North Dakota State Archives’ collections, visit history.nd.gov/data/donate_archives.html.