Some of the most fascinating features to observe in vertebrate fossils are pathologies. These are injuries or diseases the animal sustained over its life that left a legacy on the bones we collect. We like to think about these great, extinct beasts dominating the landscape — but what about the sick? The old? The injured? What happened to them? Living things in the past are just like living things today, each vulnerable to its own set of typical injuries. For the examples I provide below, I will be using Edmontosaurus, the duck-billed dinosaur (which also happens to be the same type of animal as Dakota the Dinomummy!).

Over the course of excavating these wondrous, giant “Cretaceous cows,” you would notice patterns in many of the bones. You would come across the standard bones and become more familiar with them, and thus would learn what they should look like as you gently scrape off the dirt . . . but the bones don’t always look the way they should. One of the most common bones to sustain injury is the tail — specifically what is called the spinous process. These long spikes sticking out of the centrum (main body) of the vertebrae are the same bumps you can feel on the back of your neck — just on the tail in this case. Interestingly, a lot of these tail injuries started healing before the animal died. Evidence of this healing includes breaks with a large callus (massive growth) of spongy bone around the breaks to stabilize fractures, or pockets and holes that were draining pus. The oldest animals even show evidence of arthritis on the ends of the spinous processes. Vertebrae also had a high chance of getting stepped on, perhaps while the animals slept in their large herds.

This spinous process shows just a touch of what could be arthritis, but gives you a good idea of what one of these tail bones would look like.

This broken spinous process is a mass of rough bone growth that had an active infection in it. The arrow is pointing to a lesion that was most likely an exit for pus.

Damage happened during life to this tail, with the healed result being a fusion of two tail bones together.

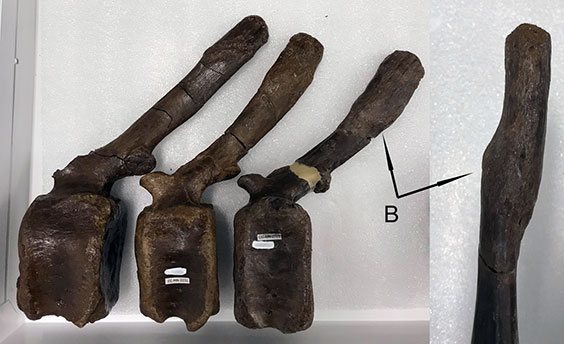

This trio of caudal (tail) vertebrae (not from the same animal) all show breaks on the top-most portion of their spinous processes. The zoomed-in spine at right shows a different angle of the break, with the bone offset while healing.

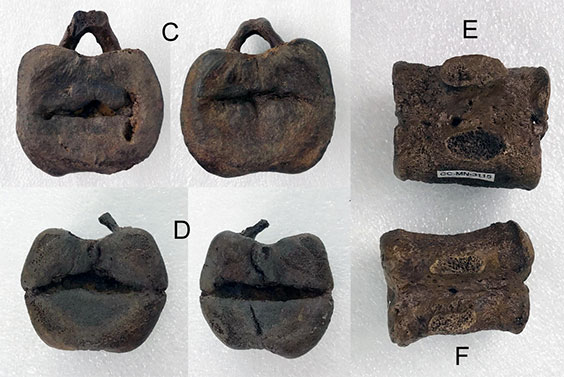

Series of caudal vertebrae with crushing damage. Vertebra C had nearly healed from a horizontal break that split the bone in two. Vertebra D was not as far along in the healing process. Vertebrae E and F split vertically in half and were riddled with infection. Pus-draining lesions can be seen scattered throughout the bone.

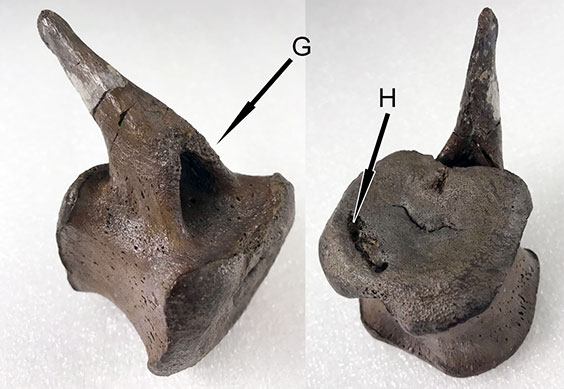

This caudal vertebra is odd — it has lost the prezygopophyses [G] that connect the bone to the one in front of it, yet the area of bone has healed. The back end of the bone also shows damage, with another lesion.

This spinous process is one of my personal favorites — just LOOK at that gnarly arthritis and infection! Crazy! AND a break on top of that.

The tail wasn’t the only bit of the animal to sustain injury. At the fossil site these came from, hand injuries were more common than foot injuries — at least you can run with a sore hand. But you become a Tyrannosaurus snack with a sore foot. Below are two hand bones that show damage. Both are set next to a normal, undamaged bone for comparison.

This hand bone shows some possible arthritis in what would have been the pinky finger.

This hand bone shows an interesting pucker on one end, which slowed the growth of the bone. It is much shorter than it should have been.