We have been promising for a while that we are going to digitize our archaeological collections – all that really means is photographing them and filing that digital photo in our electronic catalog. And we have needed to photograph one particular collection for a while, which contains upwards of 35,000 artifacts. We have a pretty good camera, we have a new photo station, and we have all the artifacts organized and ready to go. But we usually have about ten or more other projects going on at the same time. How were we going to find the time and staff to photograph that many artifacts? It seemed impossible. And then in walked David Nix.

Dave is a retired biology professor from the University of Mary and an accomplished photographer. Though he did help us out sorting artifacts as a volunteer back in 2006, it had been a while since he had worked with our division. He had just bought a new camera and wanted an excuse to try it out. He offered to volunteer for three hours, three days per week (keep in mind that this is more than an entire work day every week that he dedicates to preserving North Dakota’s history). Thanks to him, our collections staff members have become digitizing fiends! Seriously. We can’t stop taking photos.

Photographer Dave Nix sets up his next shot at the photo station in the Archaeology and Historic Preservation division’s archaeology lab.

Why is it important to have photos of our artifacts? First, it is good for their health! It is important for our staff to have instant (visual) access to our collections without having to dig through boxes looking for a specific artifact or a good example of a certain type of object. Repeatedly handling fragile artifacts increases the chances of wear and breakage.

Second, it allows us to track an object’s condition over time. We can compare a photo of an object from 10 years ago with the object today and see, for example, that it remained intact while on loan to another museum, or maybe fluctuations in humidity have caused cracking or damage.

Third, we can attach a photo to a digital artifact record that details what the object is, where it is from, and its relationship to other features and artifacts at the archaeological site. Having the photo attached directly to this information is unbelievably helpful when you are preparing for exhibits, conducting an audit, engaging in tribal consultation, developing interpretive programs, solving collections mysteries, or doing scientific research.

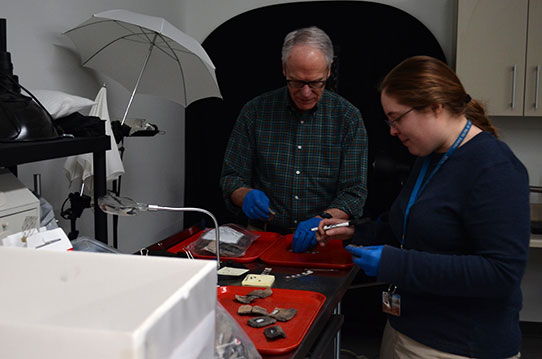

Dave Nix and Collections Assistant Meagan Schoenfelder prepping some pottery sherds for the next photo.

Finally, photos give people who don’t work with the collections access to them. We send them to researchers. We send them to conservators to diagnose condition issues. We use them in our Archaeology Awareness posters, and for presentations at professional conferences. We use them in publications. We send them to educators for inclusion in curriculum materials. We post them on our Facebook page. And we will eventually make them accessible through our website.

So when Dave comes in, here is what usually happens: first, we pull the boxes to be photographed that day. We try to keep it varied so no one gets burned out photographing a thousand horseshoes or square cut nails in a single afternoon (Though during the occasional All-Rusty-Iron-Axe-Heads-All-Day! sessions, Dave is shockingly good-natured). The archaeologist scheduled to be the photo assistant for that day decides what to photograph, writes the accession number on the photo scale, and tells Dave what details need to be documented. Depending on the object, this may include flaking scars, ceramic decoration, maker’s marks, etc. Dave adjusts the lighting and lenses, optimizing the shot for that particular artifact.

A stack of boxes waiting in line to be photographed.

After three hours, we upload them to a server set aside for collections photos (as you can imagine, this requires a LOT of data space). Then Nancy, our Division’s Administrative Assistant, labels the files, crops the photos to reduce the file size, and attaches them to the appropriate artifact record in our cataloging program. She does this not only with astounding speed and attention to detail, but often whispers, “I need more pictures!” as I am walking by her desk.

Since we started last fall, we have photographed nearly 7,000 artifacts. Only 28,000 to go! Then we will take Dave to Dairy Queen, which is all he asked for in return. When the time comes, I hope he is ready to eat a serious amount of ice cream.

See some of Dave’s recent photos of our collections below!

Left: Gastropod shell beads. Note the hole that has been punched through the outermost whorl of each shell.

Right: A bottle of Wakelee’s Camelline. This product was marketed to improve and beautify the complexion.

Left: A metal and glass pocket watch from an historic farm site in Emmons County.

Right: Historic doll parts have to be the creepiest thing we find in the field or in collections. This doll’s face looks especially menacing to me. I have coworkers who feel much more strongly about the creepiness of doll parts than I do, and who will not be happy to see that I have included them here!

Left: Ultrathin biface from our Lake Ilo collection. Incredible flintknapping skill is needed to make a large biface as thin as this one without breaking it. If you turned it on its side, you would see it is about 0.5cm wide.

Right: Pottery rim from a Plains Village site on the James River in Stutsman County.