What’s better than a 23-foot long mosasaur? A 40-foot long mosasaur! If you’ve walked through Underwater World in the Adaptation Gallery: Geologic Time, I’m sure you’ve looked up to see the giant swimming reptile called Plioplatecarpus. If you haven’t, you’re missing out. Imagine a monstrous komodo dragon with flippers, prowling the oceans as Tyrannosaurus stalked the land. The hanging Plioplatecarpus, a type of mosasaur, measures approximately 23 feet, nose to tail. That’s an impressively sized beastie. We’re currently working on another mosasaur in the lab – this one is most likely double the size of the one on display. Also found in the northeastern corner of the state, the monster mosasaur downstairs will take a long time to prepare (clean and restore). There are teeth, a few ribs, a bunch of thoracic and lumbar vertebrae – but not a lot of skull or flipper bones. They might still be hiding away in the unprepared jackets (how we transport them from field to the lab), but what we do have is of an impressive scale. Sadly, so are the concretions surrounding the bones – hence why it will take so long to prepare the fossils. To give you an example: one average-sized vertebra from the white mosasaur in the Underwater World seafloor (under the Archelon turtle) took maybe a couple of hours to prepare. One average-sized vertebra from our monster mosasaur can take up to 12 hours for one bone! Ufda.

Left, vertebra from Plioplatecarpus. Right, vertebra from our unknown mosasaur.

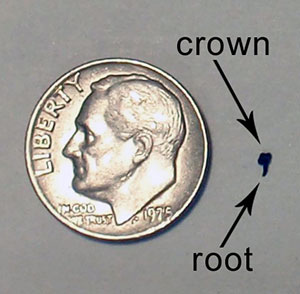

Left: Tooth and root from the mystery monster.

Right: Tooth and root from Plioplatecarpus.

Fossils may be rock, but the work is delicate. The loose shale that covers everything needs to be scraped off so we can see what we’re dealing with. Airscribes (mini hand-held air-powered jackhammers) are used under magnification. The concretions are tightly adhered to the surface of the bone, but it takes a light touch to remove them. Push too hard with the airscribe, and you drill right into the bone itself. Afterwards the bone is taken to the microblaster (sounds fun, right?), which is like a sand-blaster, but shoots baking soda. When used properly, this can remove the little bits of dust and debris that remain. Used improperly, and you can blast holes in the bone. Thus, the number one rule in the lab is Patience.

I’m sure you’ve noticed the color differences between the bones above – and below you’ll see an even more drastic color change. This is due to the types of minerals that were around when the bones fossilized Our mystery mosasaur is rich in iron – so it’s a rusty, chocolate brown (and really heavy). The Plioplatecarpus is also iron rich, but also contains sulfur, which is why you can see yellow bits (and it smells like rotten eggs when you work on them). Below are bones from yet another mystery mosasaur from the Pembina region – this one is white and flakey (and super soft) from high concentrations of gypsum.

Vertebra and flipper bones from the Pembina area, on display in the Underwater World sea floor.