The Persistent Myth of the Flat Earth and Why Historical Research Matters

In 1828 Washington Irving published A History of the Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus, in which the story’s hero audaciously proves to medieval Europeans the world is not flat. American school children ever since have learned the story of how Columbus “proved” Earth is round. Unfortunately for critical thinkers everywhere, Irving, famous for stories like “Rip Van Winkle” and “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow,” exercised a great deal of artistic license. He was more interested in telling an electrifying story than an accurate history.

The truth is, Columbus’s peers generally believed Earth was round. In fact, the awareness of a round Earth dates back at least to Pythagoras during the 6th century BC. It is unfair to generations of students to mislead them with an unnecessary story that is debunked with some basic fact checking and historical thinking.

The edge of the (flat) Earth: Here There Be Monsters. Image courtesy of www.john-howe.com

Historical thinking involves repeatedly asking, “How do we know?” It is important to be skeptical and verify information using the same methods historians use to evaluate sources. Every day we encounter and process information that needs to be evaluated and analyzed for accuracy, perspective, and potential bias. We consume a great deal of content through social media, websites, newspapers, books, movies, television, and countless other media. It is crucial for society that citizens learn how to apply historical thinking skills to this material, especially when so much, like Irving’s, might have more in common with an article from The Onion instead of an encyclopedia entry. How is a person supposed to navigate all this material and trust what they read?

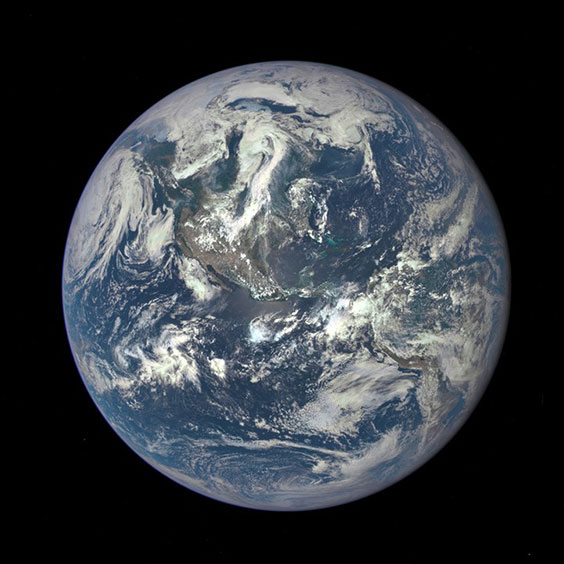

A photo of Earth from space looks pretty convincing to me. NASA image courtesy of the DSCOVR EPIC team.

Guiding people through historical thinking methods is part of my job as a museum educator. This requires a reader to understand the context of an issue, and consider multiple perspectives. When a historian sits down to read a book, reading the main text is not likely the first thing she does. A historian first focuses on the introduction to understand the point the author is trying to convey. They study the bibliography to get an idea of what sources the historian used and the breadth of their research. They also evaluate whether an author’s interpretation is supported by evidence from a variety of sources.

Before digging into the main content, we might also do a little bit of digging to learn more about the author. What are their credentials? Are they an expert on the topic? What overarching point, the thesis, are they trying to make?

Historical reading and thinking is a critical skill for readers of all ages to develop. By thinking historically and critically, we can catch Washington Irving’s mistake of playing fast and loose with the facts. We can also avoid the mistake of teaching false and misleading history. Let’s all practice thinking more like a historian and think critically about the media we are exposed to.

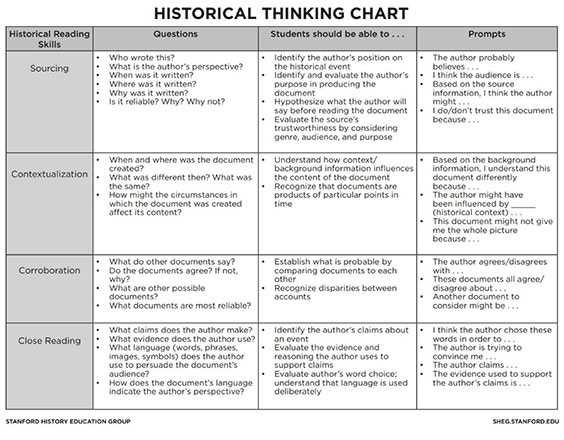

Ask these questions of images, text, and other media to avoid falling for Washington Irving–style whoppers. Image courtesy of Stanford History Education Group.