Our current The Horse in North Dakota exhibit at the State Museum features one of my favorite artifacts in the museum collections, a display horse (SHSND 1972.1635). Visitors to the Chateau de Mores State Historic Site (Chateau), located in the town of Medora, in the 1940s through the mid-1980s might remember a dappled grey horse sporting one of Medora’s (the Marquis de Mores’ wife) side saddles (SHSND 1972.715). Over the years this display horse gained the nickname “Medora’s Horse,” and many stories about its origins have been told.

The display horse SHSND1972.1635 in the hunting or trophy room at the Chateau de Mores State Historic Site 1971. Photo by Norman Paulson

Medora, an experienced equestrian, and her husband built the Chateau in 1883 as their summer home for a few years. One popular myth claimed that this horse was a real horse once owned by Medora and it had been stuffed after its death. In addition to being wrong, the story never explained why Medora would want one of her horses stuffed. The real story about the horse and how the State Historical Society acquired it is just as interesting, though less macabre.

Medora’s horse is actually a display horse. Much like a mannequin in a department store, this horse was used to display saddles and harnesses. It represents a gelding, standing 15.2 hands (62”) high. It is made of painted gesso over a canvas “hide” stretched over a wood and metal frame, with a real horse tail attached to a wood dowel and a real horse hair mane. It has glass eyes and cast iron ears. Each wooden hoof has a real horse shoe attached. The whole thing is mounted on a wooden platform on wheels. The lower jaw, ears, and tail of the horse are removable to make “dressing” it easier.

The horse was on display at the Chateau from the early 1940s until the mid-1980s when it was moved to the North Dakota Heritage Center in Bismarck in preparation for renovations to the house. We knew very little about this horse or where it came from. A chance reading of the newsletter of the Maryland Historical Society in late 2000 gave us our first clue. The newsletter had an article in their “Recent Acquisitions” section about Frosty Morn, a model horse they had just received. Frosty Morn was a duplicate of our horse. I learned that display horses like this one were made in the late 1880s to 1890s by the Toledo Display Horse Company in Toledo, Ohio. We now knew who made our horse and when.

The next part of the story came when I told the Chateau supervisor at the time, Diane Rogness, about my find. She sent me a copy of an article written by Harry Roberts in January 1978. Roberts was the first Chateau de Mores State Historic Site caretaker from 1941-1966. Roberts wrote about how he bought the model from a woman who lived on the south side of Dickinson. Roberts bought it for $10, though she claimed she had “$150.00 tied up in it, but it was of no use to her…” He loaded the display horse on a flatbed trailer to take it to Medora. We can only imagine the odd looks he must have received from passing motorists by hauling what looked like a real horse on a flatbed trailer. Roberts also tells of meeting with a friend, Joe Fritz, who was the chief of Police in Belfield at the time. Roberts writes, “I said to Joe that I had a horse in my trailer, and I was going into Billings County with it, maybe I should have a ‘Brand Inspection.’ As quick as Joe saw the model, ‘Why that is the horse that used to be in the Zimmerman’s Harness Shop!’” This gave us another clue to pursue. While the woman in this story was unnamed, she was possibly Minerva Zimmerman, widow of William J. Zimmerman, the owner of Zimmerman’s Harness Shop.

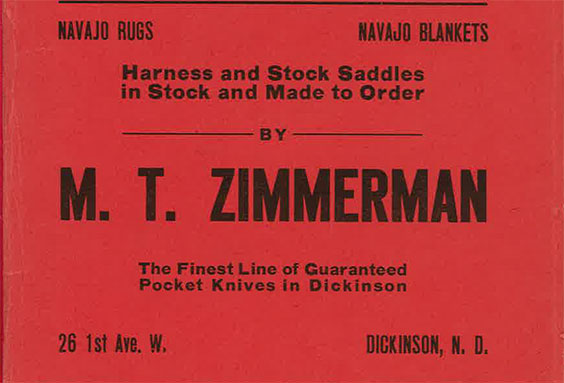

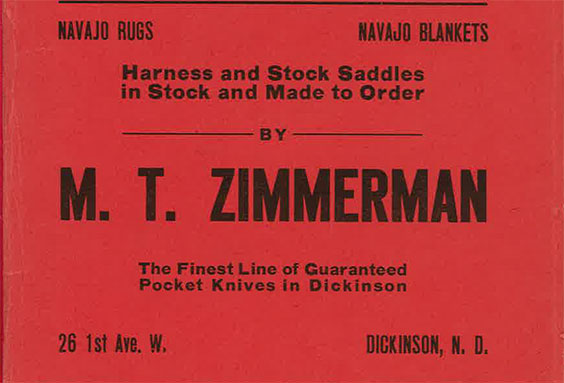

State Archives was the next place to look. There we found information about M.T and William J. Zimmerman, the father and son who opened M.T. Zimmerman Harness Shop in Dickinson, about 30 miles from the town of Medora, around 1898. The business continued to operate until William’s 'death in 1928. Advertisements like the one below indicate that they also sold a variety of goods including Navajo rugs and pocket knives. A display horse like this one would have been an excellent mannequin for showing off the saddles and harnesses Zimmerman made and sold.

Dickinson City, Stark and Dunn Counties, North Dakota, Directory, 1914-1915, Vol. 3, (Norfolk, NE: Keiter Directory Co., 1915), p. 118. State Archives 917.84/D560

We now have a richer story around this display horse than the rumor that it was just a stuffed horse. We know where it was manufactured, who manufactured it, and when. We know who brought it to North Dakota and why. We know how and when it got to the Chateau de Mores State Historic Site, and the names of the people and businesses involved.

While the display horse has been a fun and interesting part of collections tours since the mid-1980s, we were waiting for the right exhibit to bring it out and show it off. Our current exhibit, The Horse in North Dakota, is a perfect way for you to see an item that is part of the Chateau legend, an integral part of the history of the West, and a symbol of the importance of the horse to the people of North Dakota.