Two New Exhibits at North Dakota’s State Museum Showcase Ancient Predators of the Sky and Sea

I have a variety of responsibilities within my job, all of which I enjoy. One of those duties is the development of new exhibits or improvements of current exhibits across the state. The paleontology department has recently added two new aspects to current exhibits at the State Museum at the North Dakota Heritage Center in Bismarck.

During one of our fossil digs in the summer of 2017, a very large bird claw was collected. After some careful comparison to modern bird claws, we determined that this fossil claw was most likely from a bird closely related to the modern Golden Eagle. This fossil bird (Palaeoplancus) lived during the Oligocene Epoch, approximately 30 million years ago. It was a large bird, very similar in size to its modern Golden Eagle relative, and probably would have been one of the dominant predators of the time.

Bird fossils are rare and tell a unique aspect of the story of past life in the region. For this reason, it is important to share this rarely told story with the public via exhibits. The paleontology department purchased a cast of a modern eagle skeleton and hung it in an attack/diving position. It is hanging in a way so that it seems to be chasing one of its likely prey animals, the small horse Mesohippus. The fossil claw is also on exhibit as well as a cast of a modern Golden Eagle claw for comparison.

View of the Oligocene bird Palaeoplancus diving after its prey animal Mesohippus.

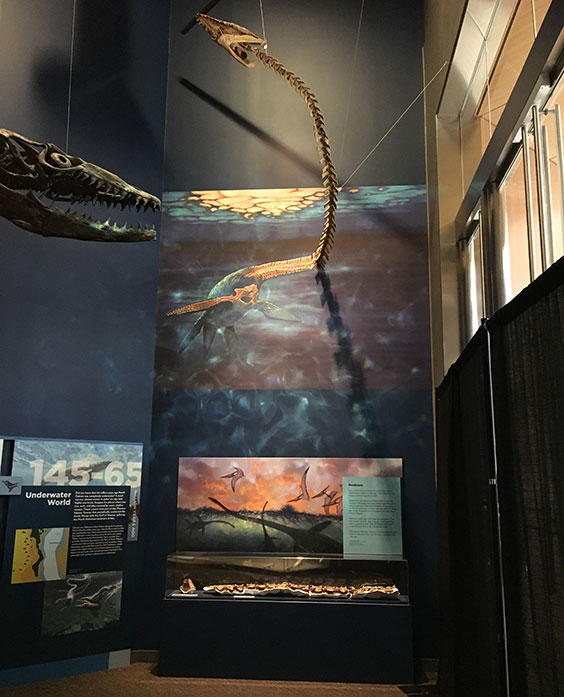

The second addition to an exhibit is the incorporation of a new mural, cast, and exhibit case with specimens into the Underwater World in the Adaptation Gallery: Geologic Time. After being collected in southwestern North Dakota and then stored at the Pioneer Trails Museum in Bowman, ND, for more than 20 years, a partial skeleton of a plesiosaur was brought to Bismarck in 2016. Plesiosaurs are a group of long necked marine reptiles (not dinosaurs) that were swimming in the Cretaceous seas when dinosaurs were roaming the Cretaceous lands. Plesiosaurs and mosasaurs lived at the same time and were both likely the dominant predators of their time, feeding on fish and likely anything else they could catch. Plesiosaurs are rare finds as fossils. Large predators tend to be relatively rare in the fauna they are a part of, and that rarity translates to the fossil record as well. The specimen we now have on exhibit is the most complete specimen ever found in North Dakota, and it is comprised of less than 10 percent of the entire skeleton.

Part of this exhibit consists of a new mural depicting part of the animal. Paleontologist Becky Barnes discussed painting this mural in her last blog post. Another part of the exhibit consists of 38 casted neck vertebrae and a skull of a plesiosaur, mounted in such a way to depict a seamless transition between the fleshed out mural and the skeleton mount. The last part of the exhibit is the actual fossil. We have on display a measly 15 vertebrae from the neck, which likely consisted of 70 neck vertebrae in the living animal. All of these pieces together will enhance the story of underwater life in North Dakota 80 million years ago.

The new plesiosaur addition to Underwater World at the State Museum in Bismarck. The mural and cast depicting the animal are above the fossil specimen in the exhibit case below.