Cold War Historic Site Connects with Today’s International Events

During the winter seasons at Oscar Zero, there are fewer visitors, and only the breeze at times breaks the silence of a prairie resting between harvest and planting. We have welcomed a steady share of guests with an interest in the Minuteman missile system through March, though, and questions arise inevitably concerning tensions with North Korea.

“Have any townspeople expressed interest in coming out and going downstairs during an attack?” (No)

“Could this site ever become reactivated?” (No)

The questions are often asked with a feeling of curiosity rather than worry.

It is an interesting time, as many Cold War thoughts have come back to the forefront of the news. Sweden recently announced distribution of civil defense pamphlets to millions of households due to Russian activities, something that has not happened since the end of the Cold War.

On January 13, 2018, a ballistic missile warning was mistakenly broadcast in Hawaii, causing great concern and reminding all of us that nuclear weapons have not been confined to the history books.

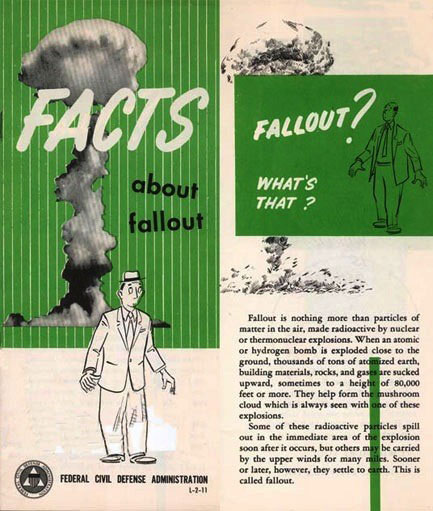

"Facts About Fallout" by the Federal Civil Defense Administration provided tips on how to deal with fallout and radioactivity

Oscar Zero is a unique part of the State Historical Society of North Dakota system due to its study and interpretation of the state’s expansive Cold War history. We have civil defense pamphlets from the 1950s and 1960s (Perhaps our favorite is “Facts about Fallout,” with a cover showing a man in a porkpie hat nervously looking up as a mushroom cloud forms behind him). The Cooperstown siren blares momentarily at noon; during the Cold War and beyond its purpose is to warn of a tornado, another type of civil emergency, or even a nuclear attack.

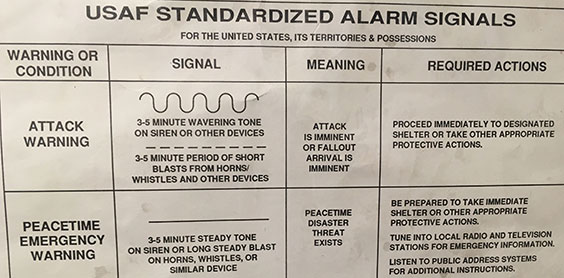

An "Outdoor Warning Siren" in Fargo. More often designated as tornado sirens across the state than a "civil defense siren," a warning on the City of Fargo website denotes, "When you hear the sirens: Immediate seek shelter indoors and turn on local media; do not assume there is no emergency because skies are clear."

Today, Minot Air Force Base’s B-52 bombers and Minuteman III missiles carry on the state’s historic mission of nuclear deterrence – a word that is an important part of any tour here at the site. Deterrence has not changed much since Oscar Zero’s Minuteman missiles stood ready in late 1966. North Dakota continues to be a part of America’s strategic vanguard.

A document explaining the differences in "attack warning" and "attention alert signals" from sirens

Considering the news from Hawaii, Sweden, North Korea, and elsewhere, perhaps the old adage of “History repeats itself” is true in some regards. Much has changed since the Berlin Wall fell in 1989, but many effects of the Cold War linger on.

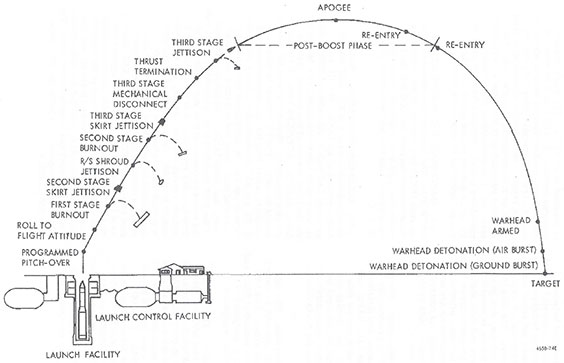

From the WS-133b (Minuteman II missile) manual at Oscar-Zero. An explanation of a Minuteman mission from launch to impact. It was approximately a 30-minute journey from November-33 east of Cooperstown, ND, to the Soviet Union.

Guest Blogger: Robert Branting

Robert Branting is the site supervisor at Ronald Reagan Minuteman Missile State Historic Site near Cooperstown, North Dakota. Aside from providing site management and public tours at Oscar-Zero, Robert is thoroughly fascinated with Cold War history and is completing work on a book on the history of a Strategic Air Command base in Nebraska. He enjoys reading, interviewing veterans and exploring Cold War sites.

Robert Branting is the site supervisor at Ronald Reagan Minuteman Missile State Historic Site near Cooperstown, North Dakota. Aside from providing site management and public tours at Oscar-Zero, Robert is thoroughly fascinated with Cold War history and is completing work on a book on the history of a Strategic Air Command base in Nebraska. He enjoys reading, interviewing veterans and exploring Cold War sites.