Restoration of Fort Totten Hospital/Cafeteria Ongoing

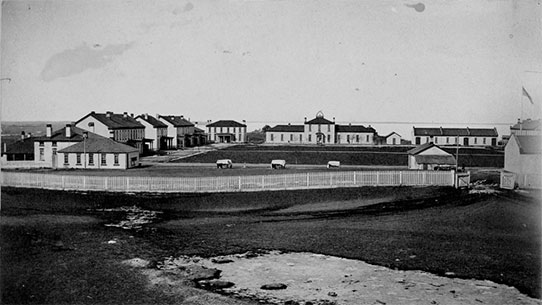

Fort Totten, pictured in 1878. The hospital, with its unique dome, can be seen in the center of the photo. SHSND B0037

Work continues on the restoration of the historic hospital/cafeteria building at Fort Totten State Historic Site. One of the largest buildings at Fort Totten, it operated as a hospital and chapel during the time the site functioned as a military post. After the military abandoned the site in 1890, it became a boarding school for Indian children, and the hospital was converted into the cafeteria and kitchen. Today, the hospital/cafeteria is home to the Lake Region Pioneer Daughters who have housed their museum and collection at the site for over 50 years. In preparation for contractors, SHSND staff worked with the Pioneer Daughters and volunteers from the Lake Region Heritage Center to carefully pack and relocate the extensive collections in the building. Once the collections were moved, contractors from RDA Inc. (Fargo) began rebuilding a central load-bearing wall that was in desperate need of repair. Over several years, the wall had begun to shift and bow precariously and was, at that point, structurally unsafe. The wall was completed in November 2015, making room for mechanical and electrical contractors who are currently installing a new HVAC system and updating electrical systems throughout the building.

In October 2015, the central load-bearing wall in the hospital/cafeteria was completely rebuilt.

With a $500,000 appropriation from the 2015 North Dakota Legislative Session and a commitment of $100,000 from the Fort Totten Foundation, the work on the building will progress much further than the State Historical Society had previously anticipated. Designs for a new exhibit space, which will interpret the hospital, cafeteria and the Pioneer Daughters collection, is underway. The State Historical Society is also working closely with the North Dakota State Information Technology Department to best determine the technology needs for the building and how to best anticipate the long term needs for the site.

The hospital/cafeteria at Fort Totten State Historic Site pictured present day.

The summer of 2016 will likely see the completion of the electrical work, first story window restoration, interior painting, floor refinishing, installation of the HVAC system, and exhibit development. We also anticipate the restoration of the historic dome that sat atop the building if funding allows. Recent research suggests the dome (pictured in historic photographs) was used as an ether dome for surgeries during the military post era at the fort—providing much needed light in an era before electricity. The addition of the dome structure will be a unique feature to Fort Totten State Historic Site. SHSND is excited about the progress of construction.