Adventures in Archaeology Collections: What Have I Been Doing?

So many projects have been going on all at once that it was too hard to pick just one for the blog. So instead, let’s look at a variety of projects.

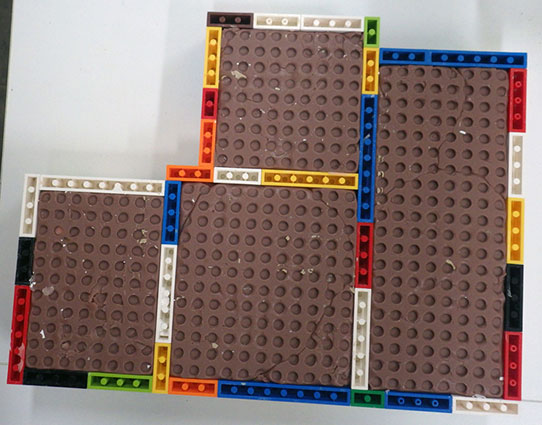

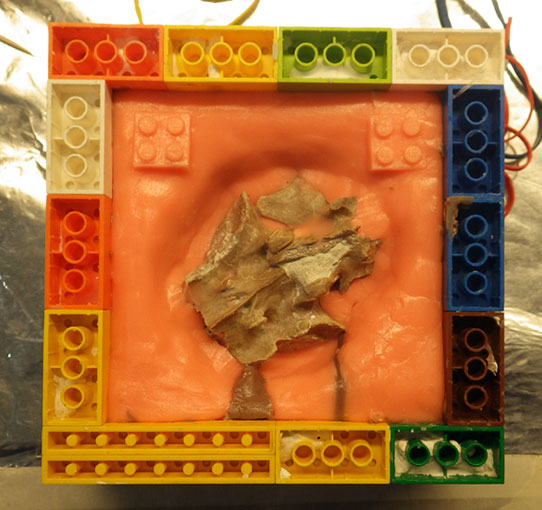

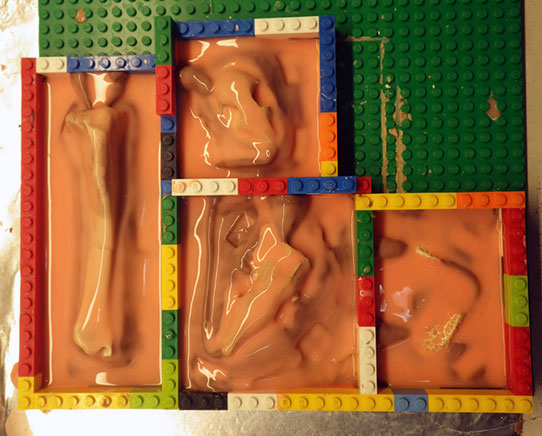

One of the projects that I am working on involves processing (labeling, rebagging, photographing as needed, and cataloging) a federally-owned archaeology collection stored here.

Work in progress.

This project involves many different sites. It also includes many types of objects--ranging from historic artifacts like glass bottles to bone tools, flaking debris, and projectile points.

Projectile points from the U.S. Forest Service collections (2012A.166.13, 2012A.166.7, and 2012A.116.1)

We are also still working on the cataloging project for artifacts from Like-A-Fishhook village (32ML2). My favorite object that we have seen recently is probably this little toy canoe.

Left: Metal toy canoe from Like-A-Fishhook village, a view from the top (12003.1719).

Right: Metal toy canoe from Like-A-Fishhook village, a view from the side (12003.1719).

It is so perfectly shaped. We also recently found a dragon! Well, a metal dragon, at any rate. It is a sideplate from a gun. Another dragon sideplate can be seen on a percussion rifle on display in the Innovation Gallery: Early Peoples at the State Museum.

Left: A metal dragon side plate from a gun from Like-A-Fishhook village (12003.1908).

Right: A .625 caliber Northwest trade gun made by Isaac Hollis & Sons with a dragon sideplate on display at the State Museum (1982.93).

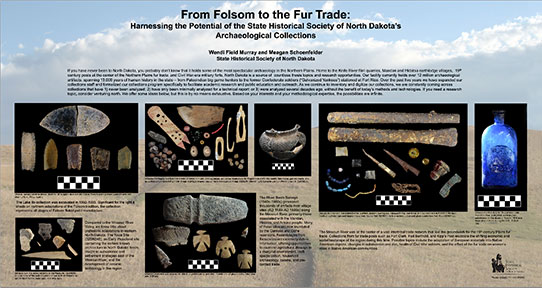

My supervisor and I also made a poster for a national archaeology conference this past month. The conference was too far away to attend in person (it was in Orlando), but at least the poster could go to sunny Florida! It was for a session that gave museums an opportunity to share what kind of collections they have available for study. Archaeology collections are meant to be researched, so this was a great opportunity to share with students and archaeologists what North Dakota has to offer. North Dakota really does have amazing archaeology, so it was fun to find pictures of objects for the poster—from Paleoindian projectiles to Woodland pottery to seeds from village sites to gun parts and glass beads from trading and military forts. A lot of work from many people went into this poster. We used photos of artifacts from the Like-A-Fishhook project as well as photos taken by volunteer David Nix (see Wendi’s blog about Dave and his work at http://blog.statemuseum.nd.gov/blog/mission-possible). We also coordinated with Brian Austin who works on graphic design for the agency—he finalized and printed the final product for us.

A small preview of what our poster for the Society for American Archaeology conference looked like.

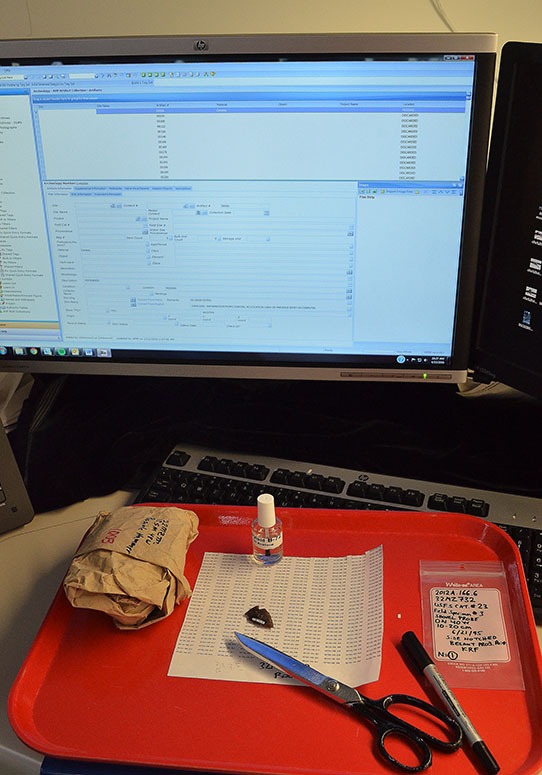

Speaking of researchers, it has been fun having a researcher working in the archaeology lab for a few weeks. This researcher is an archaeologist who is examining historic bottles from Fort Rice (32MO102) as part of her master’s thesis.

A researcher studying glass bottles from Fort Rice.

We have a sizeable collection of glass and ceramic bottles and bottle fragments from this site. It will be exciting to see what her final project looks like and interesting to learn more about life at Fort Rice.