Winter Wanderlust: Snowshoeing at Missouri River State Historic Sites

Forget about hibernating this winter. On a crisp day, there are few things more invigorating than getting outdoors for some exercise along the Missouri River. Luckily for us, some of North Dakota’s most significant historic sites also lie in close proximity. Throw in a pair of snowshoes, and you’ve got yourself the perfect outing: good for mind and body.

The best way to see an (outdoor) state historic site.

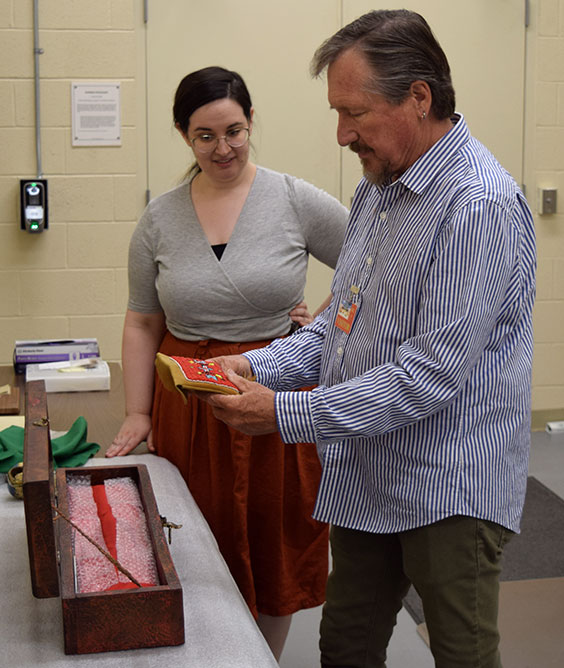

A recent out-of-state visit from my dad proved the perfect opportunity to learn more about how the Missouri River story has shaped the region’s history. With snowshoes in the trunk, Dad and I set out on a snowy day in late January to our first destination: Fort Clark State Historic Site. Located 15 miles southwest of Washburn, the site is the former home of a prominent 19th-century American Fur Company trading post of the same name as well as a Mandan village (Mih-tutta-hang-kusch) and trading hub.

After being delayed by a passing coal train, missing the turn-off three times, and a few false starts trying to strap on our snowshoes, we make our way over a picturesque stone stile (straight out of a fairy tale) and gingerly descend through a thicket of trees to the river bottoms, where we pass fresh rabbit tracks. Not far away lie fields where in warmer months Mandan women would have come to gather corn and other crops from their gardens. The snow is deep here, and I’m grateful for our fancy footwear, allowing us for the most part to travel over (rather than through) the soft banks (yes, there were a few tumbles). On the other side of the barbed wire fence running along the state historic site’s property line, we spot an elevated hunting blind and a tree stand strapped to a trunk, which adds a hint of danger to the milieu.

I snap a few photos, then we decide to head back up the escarpment to the first high terrace and learn more about the site. Above us a flock of geese flies by, their honks jarring the pristine white silence.

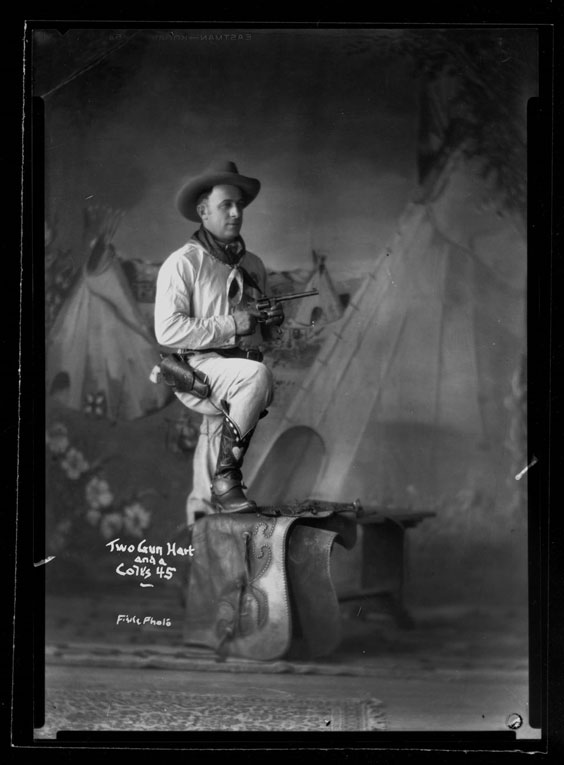

Dad at Fort Clark State Historic Site, snowshoeing in the footsteps of explorers.

At the interpretive signs, we carefully brush off newly fallen snow to read about this former crossroads of trade and once-vibrant cultural confluence. During its three decades of existence, Fort Clark attracted a remarkable stable of high-profile visitors (John James Audubon, George Catlin, Prince Maximilian, and Karl Bodmer among them).

But the same steamboats that brought visitors and goods also carried the smallpox that would decimate the Mandan community in 1837. The following year, the neighboring Arikaras moved into the village. After Fort Clark burned in 1860, its employees worked out of the nearby Primeau’s Post, which had been acquired from a competitor. Surface features at the site indicate the archaeological remains of the trading posts and the earthlodge village.

As I finish my loop around the interpretive panels, the wind and snow whip up something fierce. Small wonder why in colder months the Mandans resided in winter villages in the protected wooded river valley. Visitors these days can take refuge in a small fieldstone shelter on the site built by the Civilian Conservation Corps in the 1930s. I duck inside and sign my name in the guest book (hooray for being the first visitor of 2022!) then hurry back to the warmth of the car, where Dad has long since repaired.

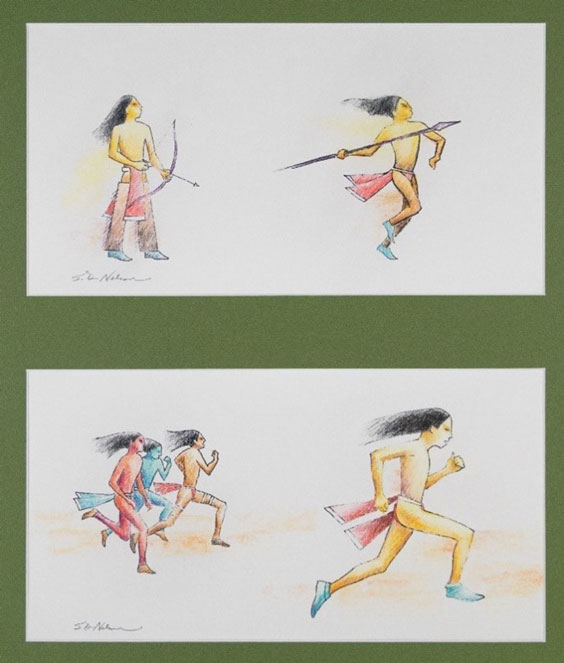

Prior to returning to Bismarck, we stop off at the Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site in Stanton, a hidden gem with a strikingly designed abstract visitor center meant to suggest a bald eagle. We pull up minutes before closing but still manage to take in a small exhibit on the culture and lifeways of northern Plains American Indians, and thanks to the lone National Park Service employee on duty even sneak a peek inside a reconstructed earthlodge out back. Dad is duly impressed.

The next day is bright and clear, and we drive 25 miles south of Bismarck to Huff Indian Village State Historic Site, just down the road from the Huff Hills Ski Area. Snow has collected near the entrance, and the car soon gets stuck in a literal rut until a shove or two by Dad, summoning his inner native North Dakotan, frees us.

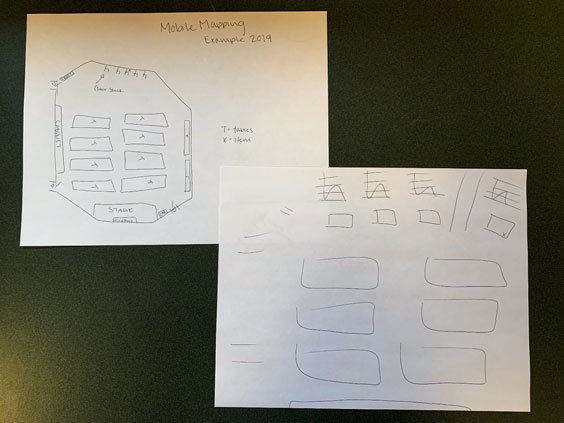

Many state historic sites like Huff Indian Village feature stations where you can transfer a stamp to your North Dakota Passport.

Once fortified on three sides by a palisade wall and ditch system, this mid-15th century Mandan settlement is sandwiched between the river and a path frequented by rafters of wild turkeys and whizzing snowmobiles. I snowshoe up to the riverbank and look out over the frozen Missouri to the snowy hills in the distance. (For the more reflective among us, or dads with aching hips, there’s also a bench for riparian daydreaming.)

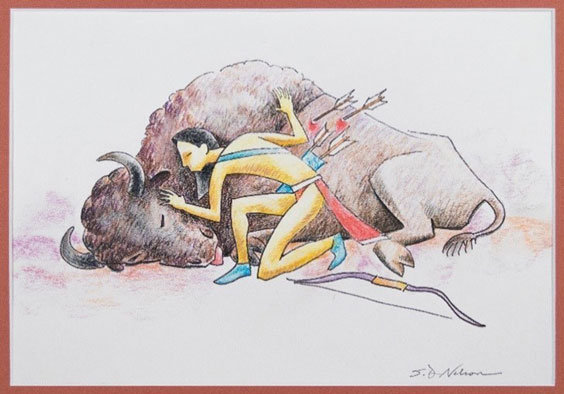

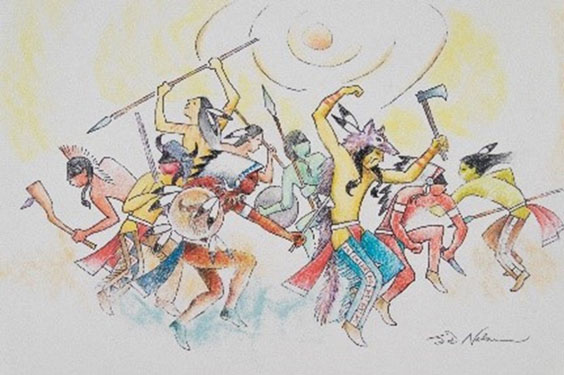

At first glance the site may appear a great white sea of emptiness, but depressions where more than 100 rectangular houses (and one slightly rounded dwelling) formerly stood, as well as a ceremonial lodge and plaza, are evident on closer inspection. Below ground, as the interpretive signage explains, cache pits (an estimated 1,700!) stored produce before mold or infestation turned some into de facto prehistoric landfills. I imagine living in this densely populated 12-acre village, with its obvious concerns of impending attack and need for a strong civil defense. I marvel at the ingenuity of the Mandans who built this community by the river, where even in the midst of threat and foreboding, dances were held and crops cultivated.

Huff Indian Village State Historic Site offers visitors sweeping views of a frozen Missouri and the hills beyond.

While Huff was only occupied for a short time (roughly 20 to 30 years), I like to think that the spirits of its former villagers are still watching from afar, as we traverse these landscapes in much the same way as upper Plains people would have traveled so many years ago. Exploring Huff Indian Village and Fort Clark by snowshoe made our visits seem more authentic and evocative, moving through space just as previous generations would have done, in a different time but the same place.