A North Dakota Connection to an American Literary Legend

In processing and organizing collections to make them accessible to researchers, the staff at the State Archives stumbles across unique items with their own stories to tell. While many of these documents and photographs relate to prominent people from North Dakota, or those who spent time or rendered some service to the state, we sometimes find an interesting connection to an important figure in American history in unlikely places.

We recently made one such find. Probate case files are important archival records at the county level that find their way to the State Archives as county governments across North Dakota need to make room for more current records. Older records are sent to us for storage and preservation and are great tools for researchers (especially genealogists) to trace the history of an ancestor’s estate and find other relatives.

In September 2017, Barnes County transferred some of their older probate records to the State Archives. Bev Keesey, one of our volunteers, worked on processing them. One afternoon she stumbled upon Case #599 from 1885 related to Anne Charlotte Fenimore Cooper, daughter of James Fenimore Cooper, author of the Leatherstocking Series, which includes the novels The Pathfinder and The Last of the Mohicans.

Ms. Cooper’s probate case is an interesting read, as her heirs included her other surviving siblings, most who resided in and around the Cooperstown, New York, area. This begs the question: how did a descendant of one of America’s most influential nineteenth-century authors, with no known connection to our state, come to have a probate case in North Dakota? The likely answer links her to one of the major power players of North Dakota early settlement--the railroad.

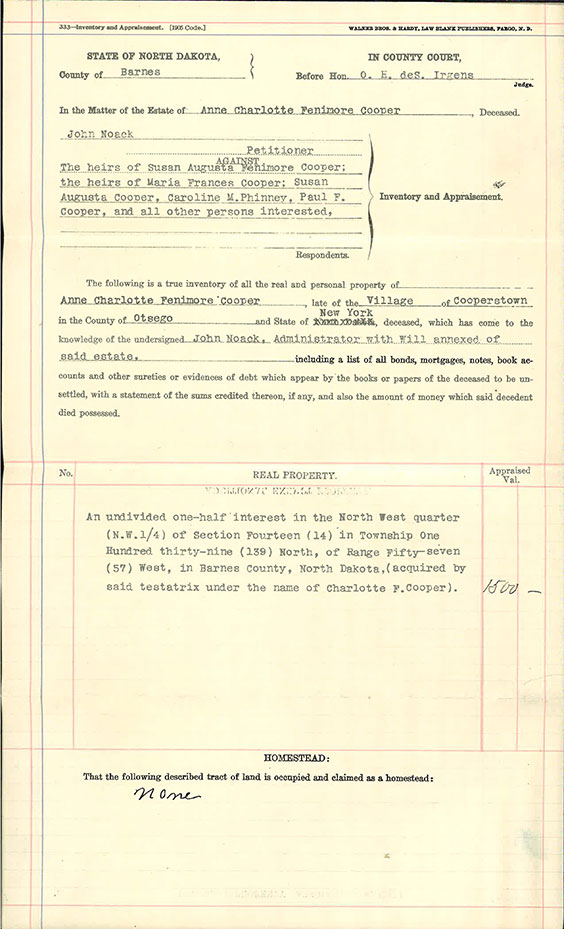

Cooper’s probate case concerned, according to several case documents, “An undivided one-half interest in the North West quarter (N.W.1/4) [sic] of Section number Fourteen (14) in Township number One Hundred thirty-nine (139) North of Range Fifty-seven (57) West of the Fifth Principal Meridian, in Barnes County, North Dakota.”1 This land is located southeast of Valley City and, based on the fact that Cooper has “An undivided one-half interest” in said tract of land, suggests that the land was part of the large swaths of land given to the Northern Pacific Railroad (NP) during the late nineteenth century along their route through North Dakota. That parcel of land was purchased in the Fargo land office by Anthony Gemmet on October 20, 1882.2

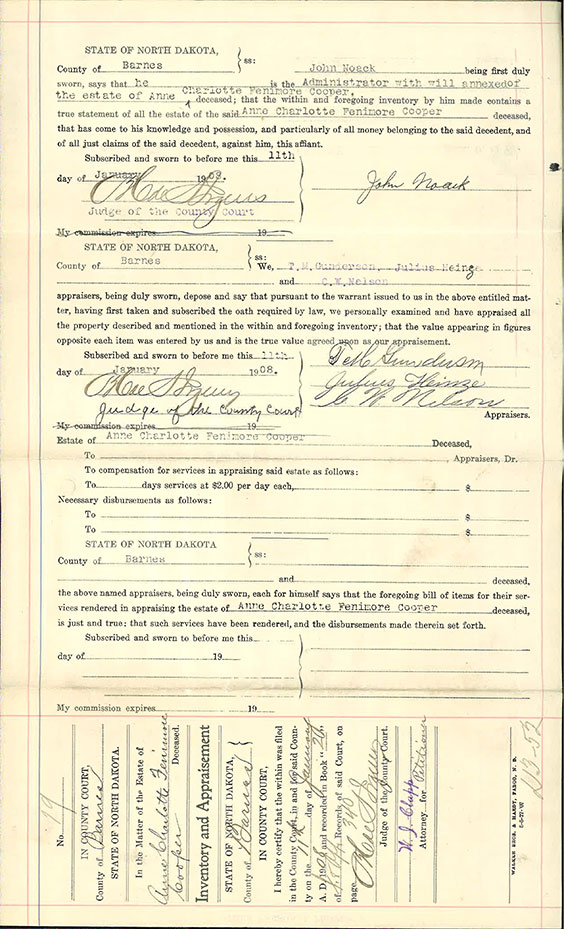

According to the case file, the interest Cooper held was valued at $1,500, which would be worth just over $39,000 today when adjusted for inflation. Further, John Noack, acting as administrator of the estate, was the petitioner to the court on the behalf of Cooper, who was deceased. As the case was probated, the land became Noack’s property, and, according to the Standard Atlas of Barnes County, North Dakota (1910), Noack (spelled Noach in the atlas) owned the entire northern half of the section in question, as well as the eastern half of section 12 in the same township.3

It is fascinating to see how a simple case related to a small piece of land in southeastern North Dakota can link investment, settlement, and the descendants of one of America’s most well-known authors. While I have no indication that Anne Cooper ever visited North Dakota, the connection of her (and by extension, her famous father) to the state is special, given the frontier nature of North Dakota in the late 1800s, North Dakota’s important role in the settlement of the West, and James Fenimore Cooper’s love of the frontier in American history.

View a PDF version of the case file.

1 Anne Charlotte Fenimore Cooper probate case file, Barnes County Probate Case Files, State Historical Society of North Dakota.

2 “Patent Details,” U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management, General Land Office Records, accessed June 27, 2018, https://glorecords.blm.gov/details/patent/default.aspx?accession=ND0350….

3 Standard Atlas of Barnes County, North Dakota, Chicago: Alden Publishing Co., 1910, 55.

Guinn Hinman was a Historic Sites Manager at the State Historical Society of North Dakota.

Guinn Hinman was a Historic Sites Manager at the State Historical Society of North Dakota.