Training State Historic Site Staff (and You!) as Certified Interpretive Guides

I’ve been leading (and loving) Certified Interpretive Guide (CIG) trainings for about six years now. When I started as a historic site manager this spring, I was thrilled to be asked to lead them for the State Historical Society as well. CIG, a four-day course designed by the National Association for Interpretation (NAI), is an enriching opportunity to learn, share, and develop ideas with other heritage interpreters.

What do I mean by heritage interpreters? You may also know them as docents, tour guides, rangers, or public historians. They’re the people who translate technical knowledge into inspiring informal education for kids, tourists, or your family from out of town. You might encounter an interpreter at a museum, local or national park, botanic garden, zoo, aquarium, online, or, of course, at a historic site.

I’m passionate about interpretive training like this for two reasons. First, our visitors get a better experience. Second, it shows that interpretation is not just a hobby, it’s a profession.

So what will participants learn? There’s a lot to it, but there are six central attributes of effective interpretation that we spell out as an acronym: POETRY.

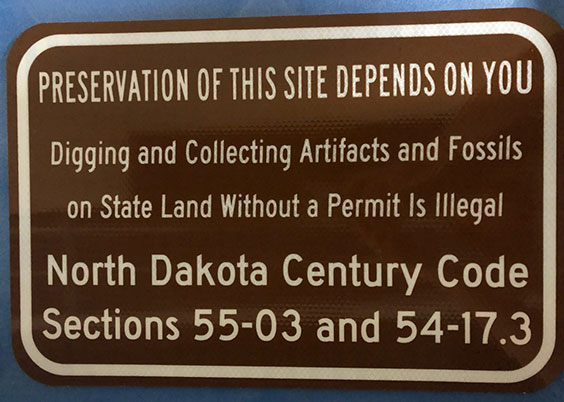

Purposeful. Interpretation solves problems for an organization like the State Historical Society. When a historic site needs maintenance, when common visitor behaviors may threaten a historic resource, or when funds need to be raised, interpreters communicate the need. CIG training gives guidance on how to develop an objective for a given interpretive program and how to measure its success.

These window turn buttons from around the Former Governors’ Mansion were each installed at different times. Though seemingly insignificant, they help site staff interpret when different changes and remodels were made to the house. Photo credit: Johnathan Campbell

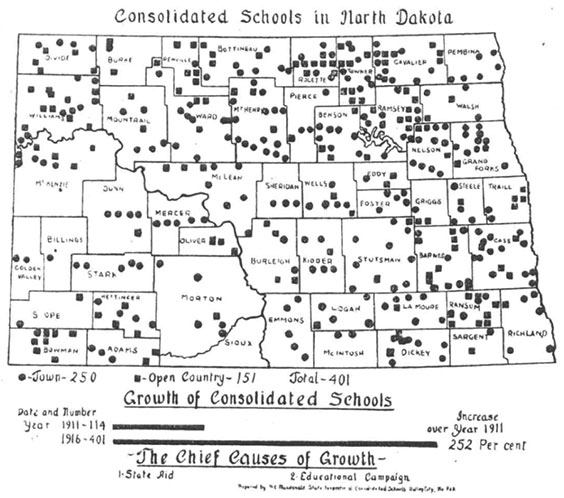

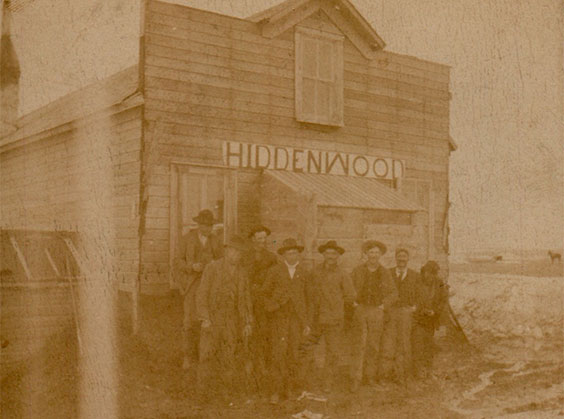

Organized. The invisible side of interpretation is the hours spent gaining technical knowledge. In the short time I’ve been here I’ve repeatedly been amazed by the incredible amounts of research our historic site staff do. They find the answers to seemingly impossible questions using plat maps, photographs, artifacts, unpublished texts, information from descendants, eyewitnesses, or even physically trying historic processes. But like a filmmaker with hundreds of hours of raw footage, the challenge is to figure out how to pare, sort, and organize a wealth of content into something the public can enjoy. In CIG, interpreters develop techniques to hone their content into one cohesive story.

Interpreters know that enjoyable learning is the most powerful. Photo credit Rob Hanna

Enjoyable. Written and spoken words are an incredibly efficient way to consolidate information (I’m using written words right now, after all!) But they don’t always work for young children, people who don’t speak the language, or people with certain disabilities. CIG trainees discuss and explore creative ways to communicate with smells, images, video, flavors, music, textures, and more. Very often we think of these as supplements to the written word, but in fact these “learning modalities” can sometimes communicate even more than the written word and live longer in the visitor’s memory. For instance, a person who reads about how to set up a tipi doesn’t know more about it than the children who set one up a few weeks ago at an event at Whitestone Hill.

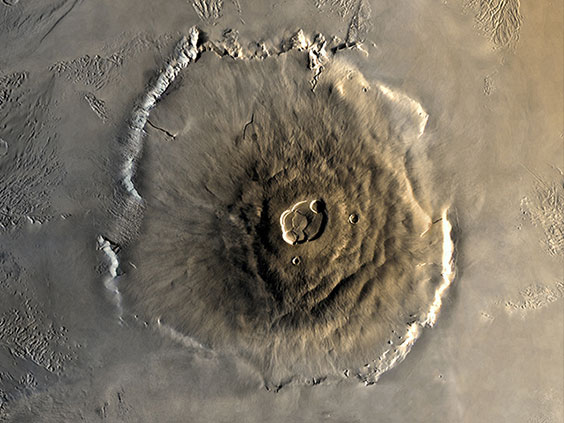

Interpreters show how their resource fits into “the big picture.” Photo credit: Rob Branting

Thematic. Thematic interpretation ties the entire message to one “big idea.” Every state historic site we have has a “big idea”—the reason that place matters. Welk Homestead shows how an immigrant family achieved the American Dream. The Chateau de Mòres shows what happened when an aristocrat tried to make it in cattle country, one of the least aristocratic places on earth. Ronald Reagan Minuteman Missile shows how rival superpowers with the power to destroy the world made uneasy peace instead. Effective interpretation ties what the visitor is learning to that big idea. And the big idea ties to the purpose referenced above.

Relevant. We explore how to better understand our visitors and tailor their experiences to their needs. Over time, it becomes easy to adapt our interpretation to the average of every visitor we meet, when in fact each visitor is incredibly different. Our visitors include children, elders, international travelers, passionate researchers, guests at an on-site wedding, and descendants of people who lived or died at our sites. In CIG, we discuss and develop ways of learning more about our visitors early on. If we can do that, it’s usually possible to delight a visitor with knowledge or an experience they didn’t even know they wanted!

You. Recent research by Robert Powell and Marc Stern shows that the passion of the interpreter is likely the single biggest factor in interpretive success. This is one of the best things about CIG training. Guided discussion among a diverse group of interpreters, each with their own experience and point of view, sheds new light on ideas they thought they already knew and validates ideas they weren’t yet ready to try. Interpreters leave inspired to try these out.

I will also be tailoring the course content to some of the unique needs I’ve seen in the Northern Plains region. Because we have many smaller institutions and organizations where formal sit-down programs and scheduled tours are impractical, we’ll practice techniques for offering visitors spontaneous experiences that still achieve all six elements of the POETRY model. We’ll also discuss Northern Plains Native American educational traditions, because following those practices help to portray Native history and culture appropriately.

We are opening these trainings to the public as well. Anyone who practices some form of heritage interpretation may find this course of interest. It will soon be listed on NAI’s course calendar. Having multiple points of view in the room only makes the course better, so if this is for you, we would love to have you join us!