Archaeology is Elemental: Geochemical Source Analysis of Obsidian Artifacts from North Dakota

Lithics, or stone tools and flaking debris, are among the most common artifacts found at archaeological sites in North Dakota. They can convey information to archaeologists about the people who made these objects, and they can also tell a much larger story of landscape use and cultural interaction. The rocks people eventually knapped into tools had to first be collected—sometimes this was done directly by the knappers themselves, and sometimes stone was acquired through trade with other groups of people. Lithic materials from North Dakota sites come from a vast area that includes the Northern Plains, Upper Great Lakes, and Rocky Mountains. Obsidian artifacts are occasionally found in North Dakota, but there are no obsidian sources within the state. Obsidian was prized by knappers for its properties. It is a high-quality, reliable stone with hardly any flaws, and it produces very sharp edges. It may have also been favored for its aesthetic value.

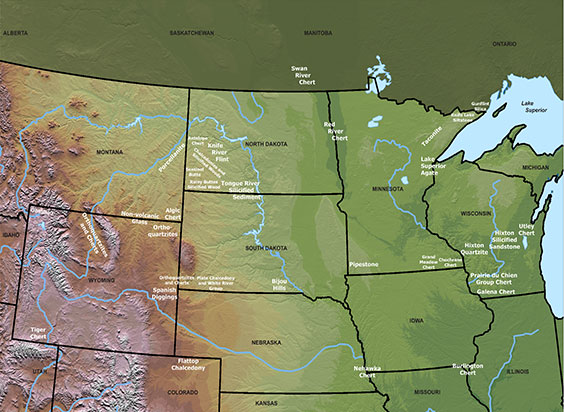

Regional lithic raw material sources. (State Historical Society of North Dakota)

Obsidian forms during volcanic eruptions when lava flows supercool upon contact with air or water, creating volcanic glass. Each volcanic flow has a distinct geologic and chemical signature, and the chemical composition of the obsidian formed from these flows is uniform throughout the source. Obsidian is composed mainly of silica (which gives it its glass-like appearance), but also contains trace elements such as zirconium, niobium, iron, and manganese. The ratios of these trace elements differ between obsidian sources, distinguishing them from each other on an elemental scale. Archaeologists specializing in geochemical techniques use instruments to analyze geological samples and determine a trace element profile for that source. Think of a trace element profile as a kind of fingerprint—although obsidian sources may be similar, no two are exactly alike. Once a geochemist has a fingerprint of the geologic source, it can be compared with artifacts made from obsidian. One of the most common instruments used to assess trace element composition is an energy dispersive x-ray fluorescence spectrometer (EDXRF). This analysis is non-destructive, which makes it especially useful for testing museum specimens.

Obsidian artifacts sent for sourcing (left to right: projectile point from Beadmaker; biface from Huff; biface from Shermer). (State Historical Society of North Dakota)

Previous research has shown that North Dakota knappers used obsidian from three main sources in the Yellowstone region: Obsidian Cliff (Wyoming), Bear Gulch (Idaho), and Malad (Idaho)1. This earlier study did not include artifacts from Mandan villages, and we were curious about trade patterns at these sites. The Mandans were key players in an expansive Northern Plains trade network during the Plains Village period, and certain villages may have controlled access to obsidian materials. Obsidian tools and flakes were selected from six Mandan villages and one Mandan campsite that date between AD 1300 and AD 1750. These 76 samples were analyzed by Richard Hughes, Ph.D., at the Geochemical Research Laboratory in Portola Valley, California.

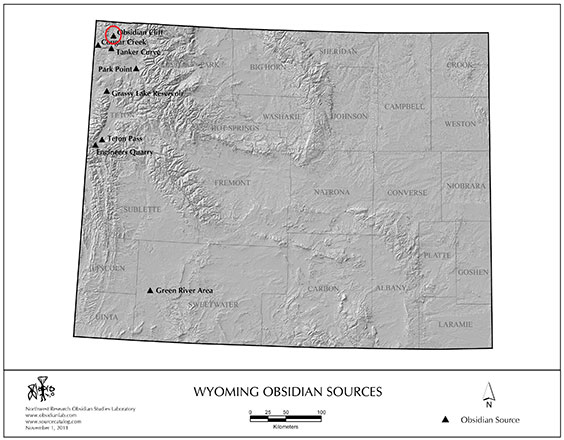

Wyoming obsidian sources (courtesy Northwest Research Obsidian Studies Laboratory, www.obsidianlab.com)

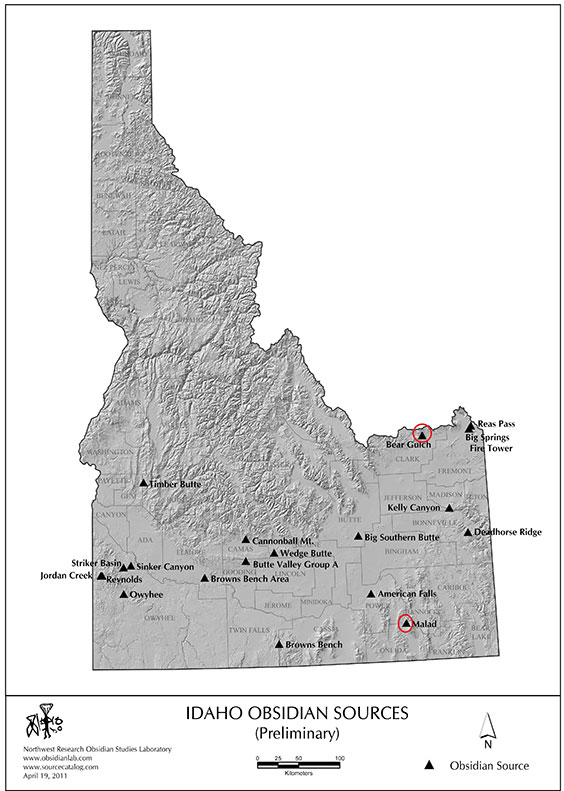

Idaho obsidian sources (courtesy Northwest Research Obsidian Studies Laboratory, www.obsidianlab.com)

Using EDXRF, Dr. Hughes concluded the obsidian artifacts from the Mandan sites came from the Obsidian Cliff and Bear Gulch sources. No artifacts were sourced to Malad. All sites but one had a combination of Obsidian Cliff and Bear Gulch artifacts, although in differing frequencies. The outlier was Huff, but only one artifact was submitted, and this was sourced to Obsidian Cliff.

What does this mean for patterns of exchange in the Mandan world? While this is a pilot study—that is, the first step of a larger project—we can hypothesize that use of Obsidian Cliff versus Bear Gulch materials at Mandan sites was not controlled by certain Mandan villages. Instead, obsidian imports into this region of North Dakota were more likely driven by the hunter-gatherers that controlled access to obsidian outcrops in the Yellowstone area. An expanded sample of Mandan obsidian artifacts will help refine our understanding of regional trade networks.

1 Baugh, Timothy G. and Fred W. Nelson (1988) Archaeological Obsidian Recovered from Selected North Dakota Sites and Its Relationship to Changing Exchange Systems in the Plains. Journal of the North Dakota Archaeological Association 3:74-94.