It’s time for the international museum dance-off! Electronic Records Archivist Lindsay Schott and Reference Specialist Sarah Walker dance through the State Historical Society of North Dakota.

Faithful readers of this blog may recall my post from last year, about our first entry into the Museum Dance off hosted annually by the blog "When You Work At A Museum."

Well—it’s back!

This, the fifth year, is a bittersweet year for the competition. It marks the “last dance”—a final hurrah for the author of the “When You Work at A Museum” blog to host the international dance-off she created. It is silly, yes, but that’s what makes it fun—and it has allowed museum communities to show off their talents, and how awesome their staff, patrons, and collections are.

Last year, we were pretty ramped up for our music video take on “Stereo Hearts,” by Gym Class Heroes and Adam Levine. Our entry is here, if you’ve forgotten it.

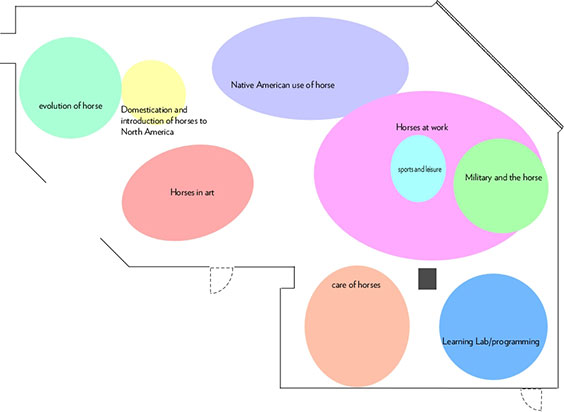

This year, our dance-off mastermind director, New Media Specialist Jessica Rockeman, decided to take a different tack—a one-take wonder (more or less). The idea was this—we’d basically dance our way from one end of the building through to the other. No cuts, or as few as possible, would occur.

The beginning of the video, filled with drama and electricity. Actually, we decided on this opening pose just before we shot the scene.

Lindsay and I were once again ready and willing. A song, date, time, and place were picked. I set up some simple choreography for everyone to do together at the end. Other staff from our multiple divisions showed up to help us. And a movie was born.

Okay, it wasn’t quite as simple as that. But it did take less time, this time around.

Jess and I did several walk-throughs of the building, scouting out how we would move with the camera and each other. This was conducted sans camera, so any staff walking along saw Jess holding a phone and walking backwards, her head swiveling back and forth constantly, with me essentially skipping in front of her and stopping occasionally at different spots to dance around. Then Lindsay came with, and we repeated it all again. And again. And again.

Our goal was to cover as much ground as possible, and include as many people as we could. We started in the far end of our staff area and plotted to make our way up into the State Archives, through our three permanent galleries and ended in our grand and beautiful atrium. However, no matter what we tried, we ended up just flat-out running from one end to the other.

The following conversation is mostly true, but is slightly dramatized.

“Jess,” I gasped, “We can’t just run! We need to be able to dance!”

“Yes,” Lindsay wheezed, “we’re running the whole thing!”

“True,” Jess replied, panting. “And I’m running backwards. But we need to move from here to there. Shall we try again?”

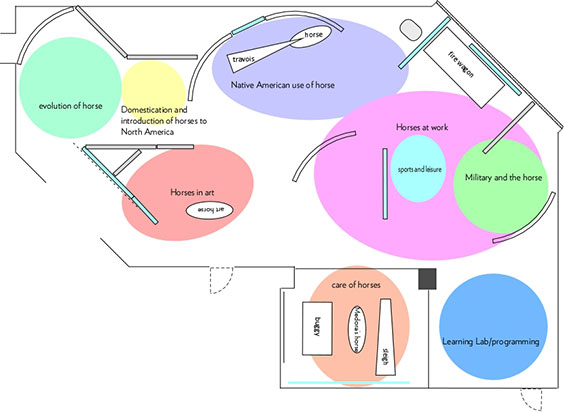

This was our cheat. This door actually opens up into more museum, but we cut and opened in the State Archives Division—we got to take a little breather, but not for long. We probably had a minute and a half rather than half a minute, this way!

So I’ll let you in on a secret. We cheated—just a little bit! We snipped some of the employee area, and we used one cut to skip some dead hallway. Technically, we walked through one door and appeared in a different section of the building than we should have. We raced through a few other areas, and we somehow made it in time to do the dance at the end in the atrium. Our one-take, no-cut video became a one-take, one-cut video. But this way, we were able to survive the song, still dance (it is a dance-off, after all), and achieve it mostly without running. (Please note, this video or blog does not endorse running in the galleries! We have strict no-running policies. But when you work at a historical society, and you are shooting a dance-off video with caution and alacrity, it may at times appear that you are slightly bending the rules. I guess we can just call it a perk of being in this specialized field.)

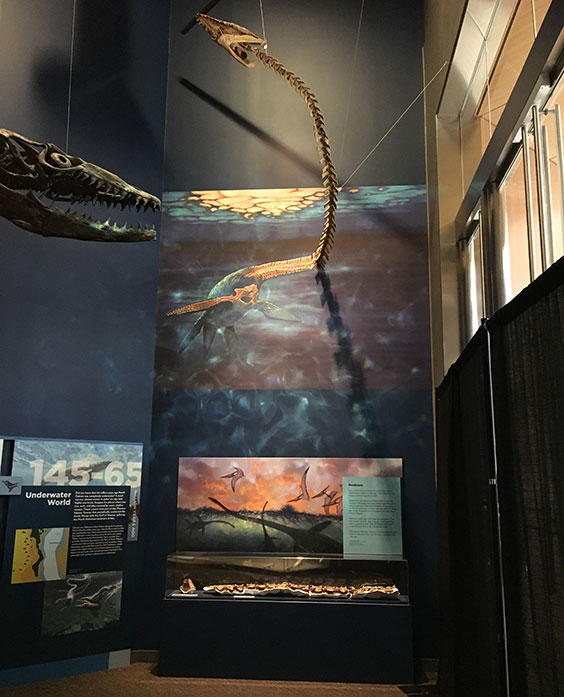

We hope everyone caught the staff cameos, especially in the first few scenes! Here is one of our museum preparators, Andrew Kerr, rocking out in the Paleo lab

Really, that was it. Lots of run-throughs and crossing of fingers for extra staff, and then the grand number that you can view on our YouTube page. It was all very different from last year’s, but it had its ups and downs. In fact, Lindsay and I felt there were several pros and cons with the video.

More cameos - Archaeology Collections Assistants Meagan Schoenfelder and Brooke Morgan returned to add their flair in the Archaeology lab

Pros:

- We spent a lot less time filming this video and felt less pressure.

- We enjoyed the making of a one-cut/one-take wonder!

- We covered a lot of ground and showcased a lot of our workplace.

- I love dancing in the atrium. We should have more reasons to do this on a regular basis.

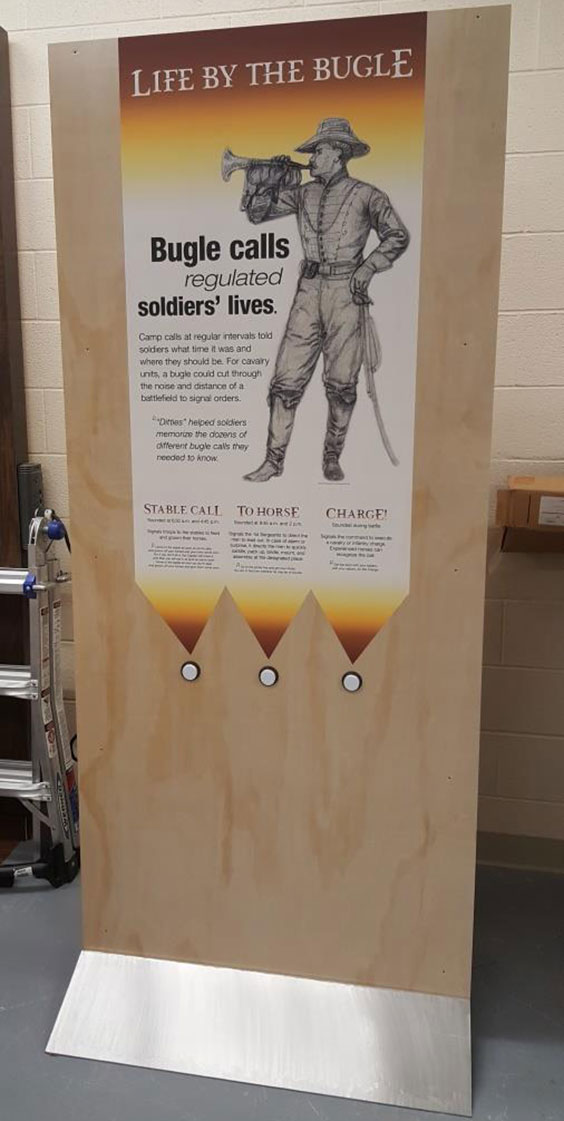

- We got to dance with a friendly dinosaur.

- Actually, we had a good group of staff come along for the ride. Also, we had an awesome group number at the end.

- We laughed. A lot.

The collision happened fairly early on, and only once—pretty good, considering how many times we had made this run by then!

Cons:

- The camera moved a bit more than we could help. You know, what with the running backwards and forwards, and all.

- We wanted to post more staff in our employee staff area than we were able to do.

- We did several practice rounds before shooting the actual one-take/one cut wonder, and many of us were out of steam by the end, with several choosing to enjoy cooling off in the sub-zero temps we had outside on that day.

- Lindsay and I almost took each other out at the beginning of the video and were gasping by the end.

We were almost done at the point this scene was shot! The finale was soon to follow.

It was fun to do this video again, and to try something different. We greatly enjoyed it! From the dancing dinosaur to the cameos of staff from beginning to end, we have a video we are pleased to share. Watch it in all of its glory, here and now!

We need your help to get out of the first round, this year! On Tuesday, May 1, at 7 a.m. CST, through Wednesday, May 2, at 6:59 a.m. CST, you can vote as many times as you want for our video. All you have to do is go to www.whenyouworkatamuseum.com and find our submission. The link will be shared again via our social media pages.

Share our video. Share our passion. Enjoy our work. And don’t forget to vote!

We made it! Jess decided early on that we needed a dinosaur in the filmed footage, and paleontologist Becky Barnes kindly helped us out—you can see her in the midst of our group in this picture. Because, who wouldn’t want to dance with a dinosaur?

This was our final group shot, where we did our moves together and then cut loose.