Inventory: A Historic Treasure Hunt

When you mention to most people that you are doing inventory, their eyes glaze over and they start thinking of their summer vacation. I am one of those odd museum people, when I think of doing inventory, I think of all the interesting possibilities the inventory might bring and “treasures” I might find. The museum collections are over 100 years in the making and contain more than 74,000 objects (with more added daily). Keeping track of these objects can be a daunting task, so we routinely conduct inventories. Many times we just check off a box saying any given object is in the right place. But every so often, something fun happens—we find a forgotten historical treasure.

One of the most exciting discoveries was the silver filigree lamp shades with pink fringe from the USS North Dakota silver service (SHSND 6068.40-53). Once thought to be missing, they are now on view in the Hall of Honors in the lower level of the North Dakota Heritage Center & State Museum.

Lamp shade, USS North Dakota silver service (6068.40)

That find, however, was recently eclipsed by the discovery of World War I–era surgical dressings made by the American Red Cross.

In preparation for our new WWI exhibits, I did an inventory of all the items donated by the American Red Cross. We have a collection of refugee clothing for men, women, and children, and we have “comfort” items made for the soldiers including knitted socks and a sleeveless sweater. We even have some hospital garments such as bed shirts (what we would now call hospital gowns) and a surgical gown, mask, and cap. These garments were made as models by the regional American Red Cross headquarters and then sent to chapters throughout the state. Along with the model garments, the local chapters received the cut pieces and directions for sewing. While we don’t have the pieces, we do have the model garments and many of the directions. But, I have to admit, I was a bit disappointed we didn’t have any of the iconic bandage rolls or surgical dressings I was reading about while researching the clothing items.

Digging deeper into our records, I found an entry for a “bandage” that came into our collections almost 20 years after the Red Cross garments. So with great anticipation and the help of a wonderful volunteer, we went looking for the bandage. We found a box with the artifact number we wanted, but inside we found only odd textile items and no obvious bandage roll near the top. Disappointed, I figured we might as well pull the whole box and clear up any discrepancies inside.

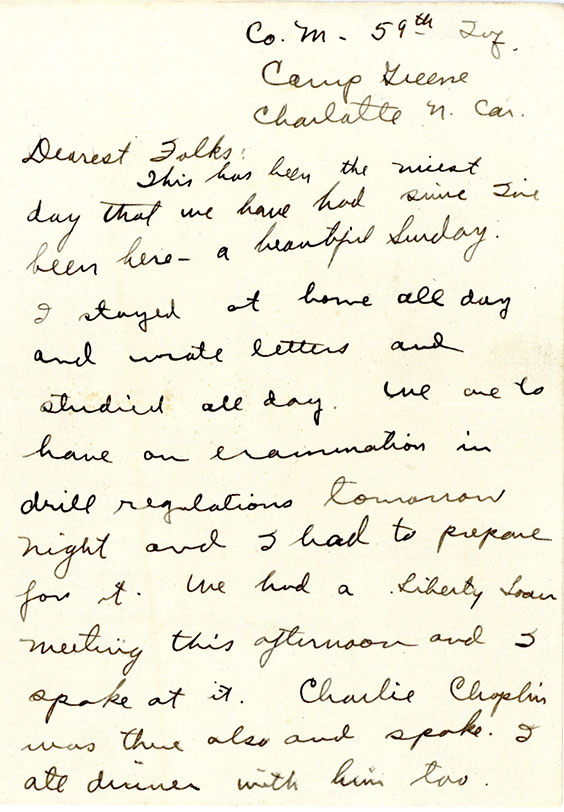

The first step was to search our paper files—but there was no file in the filing cabinet. Next, I checked the old card file. Prior to a computer database each artifact was given a 3x5” card with the artifact’s information, which hasn’t been updated since the 1980s. This card was the key to the treasure chest. It read, “Bandages, Red Cross, miscellaneous used during war. Received from Red Cross; October 15, 1937.” Instead of one bandage, we found 21 assorted bandages and surgical dressings that had never been properly cataloged. It was exciting as we found each piece nicely labeled: irrigation pad, gauze sponge, gauze wipe, shot bag, pneumonia jacket, and—YES!—a roll of gauze bandage! There is even a triangular bandage, a “many tailed” bandage, a “scultetus” bandage (a bandage used to protect, immobilize, compress, or support a wound or injured body part), and, one of my favorites, a “Paper-backed Irrigation Pad” (SHSND 5991.5).

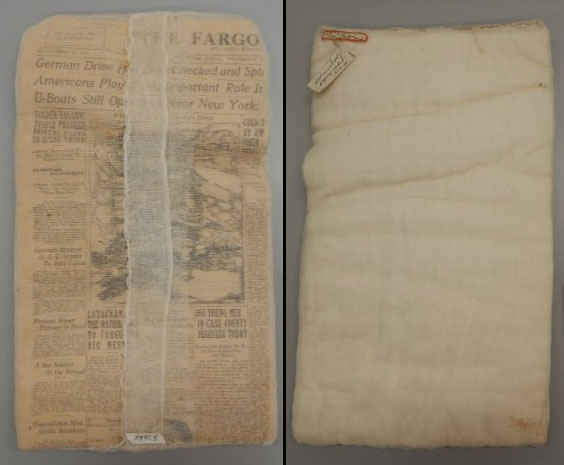

The paper-backed irrigation pad was a wealth of information. The original catalog card had the phrase “used during war,” and the donation date of 1937 suggested these might be WWI-era items. They could have been from the Spanish-American War or the Mexican Border Conflict, as North Dakota troops served in both conflicts. As the name suggests, the paper-backed irrigation pad has paper as a backing material. But this is not just any kind of paper—it is a newspaper! Lucky for us, it was the front page of the Fargo Forum. While the full date was missing, enough of the headlines and one obituary made it possible for our State Archives team to find the date: Wednesday, June 5, 1918. YES, these are WWI-era items! We also learned the pad was made in or near Fargo, North Dakota, sometime between June 6 and November 11, 1918, but probably closer to the June date. Historic treasure indeed.

Front and back of Paper-backed Irrigation Pad (5991.5)

Seeing all of these medical dressings makes me grateful for modern medicine and sterile conditions, and it makes me appreciate even more the homefront efforts that went into the Great War. The patriotic fervor that swept the nation had young and old men and women knitting scarves, sweaters, and socks for soldiers. But most of all I appreciate the legions of women who worked tirelessly to make hundreds of thousands of items to meet the needs of soldiers and refugees throughout Europe.