3 Tips for Searching State Archives Collections on fiNDhistory

The State Historical Society of North Dakota’s new searchable database—fiNDhistory—allows the public to view, browse, and search holdings as they are added, scanned, and edited in real time. Here are three tips to search for State Archives collections on the site:

1. Search within a specific directory

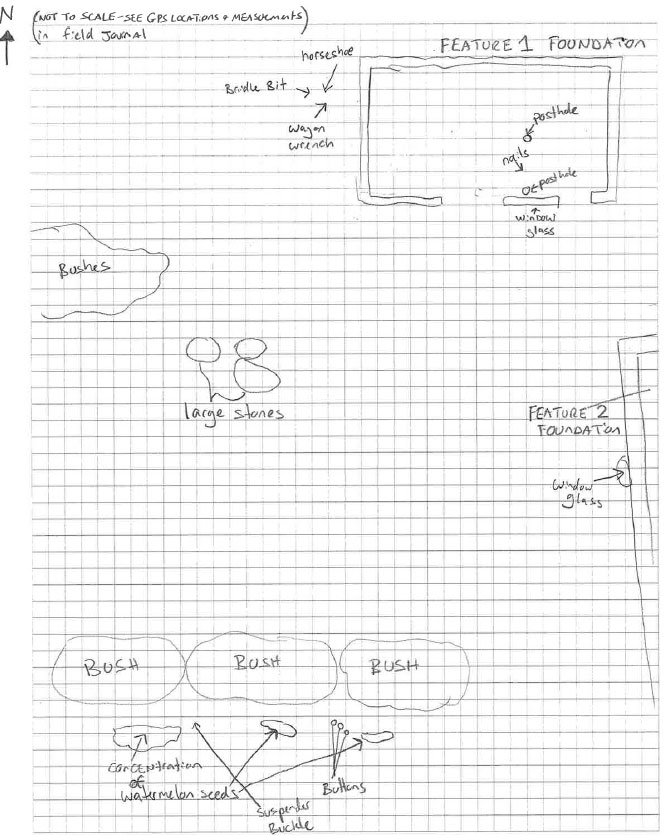

The State Archives holdings include local and state government, manuscript, photograph, and library collections. These unique collection types are stored and managed separately on-site and appear as distinct searchable directories on fiNDhistory. In addition to these directories, there are indexes for State Historical Society publications (titles are listed on the landing page) and Foundation tributes managed by the State Archives. More indexes will likely to be added in the future.

As an alternative to a global search, which includes all directories (at all levels), you can search within a specific directory to quickly return a manageable list of results. On the home page, click on the desired collection type/directory to search within it. There, you will find a search box where you can type your term.

Archival directories and indexes (highlighted) may be searched globally or individually.

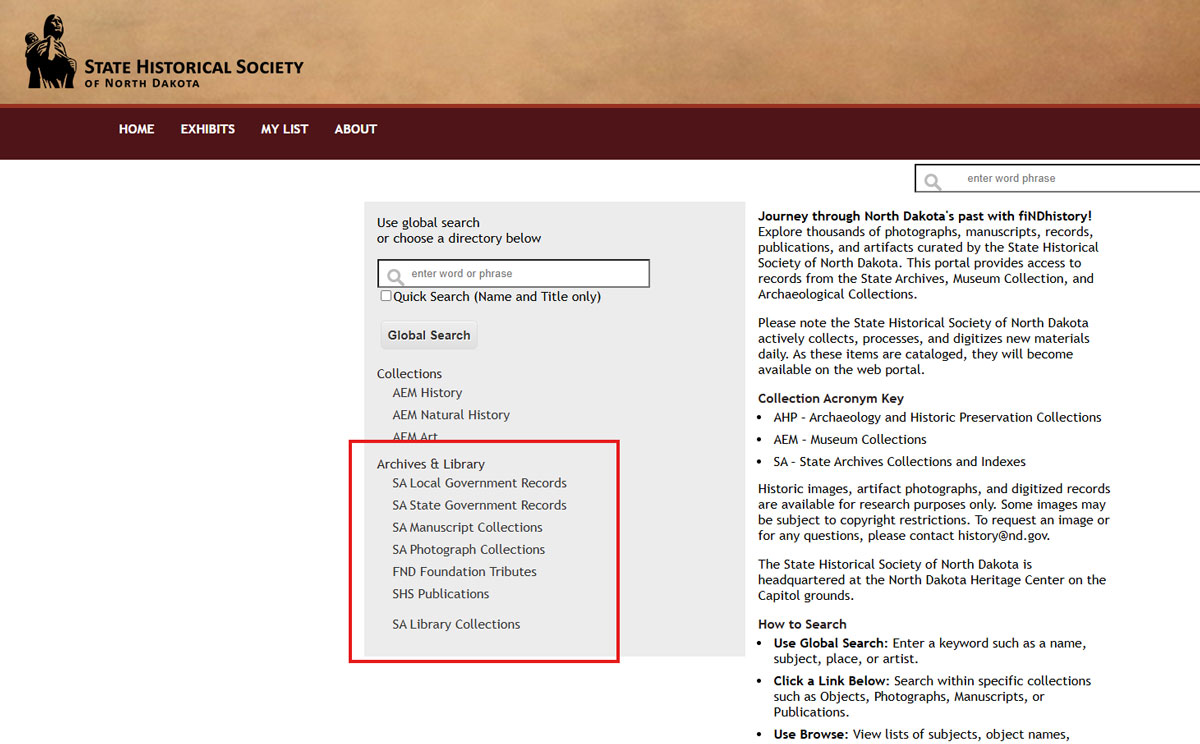

Data within fiNDhistory is set up to mirror how collections and materials within them are physically organized. The library collection is keyword search only, but searches within the other collection types include the option to narrow the search by archival level (found below the search box). Collection level records describe each collection as a whole, providing an overview and selected terms that apply to all boxes and materials within. The archival level “collection” filter searches this broad collection-level information. Series is an intellectual level of description used by archivists that is great for physical organization of collections but the least useful for searching. File unit records include titles and dates of the contents of each folder in every collection. This level is probably the best for searching because most collections have file descriptions. Additionally, a file unit search may pull results that a collection level search would not. Finally, the archival level item searches all item records that have been created within each collection. Note that this will not search for every single item in the archives, only the items that have been described. The quantity of item records vary widely across directories: Photograph and manuscript collections often include item records, while local and state government collections rarely do. The archival level dropdown also allows for a search of all levels.

Drop-down option to select the level of the archival record to be searched.

It should be noted that all collection types contain photographs, but photograph collections consist of only photographs. Audiovisual recordings are primarily found in manuscript collections (but are also in local and state government records).

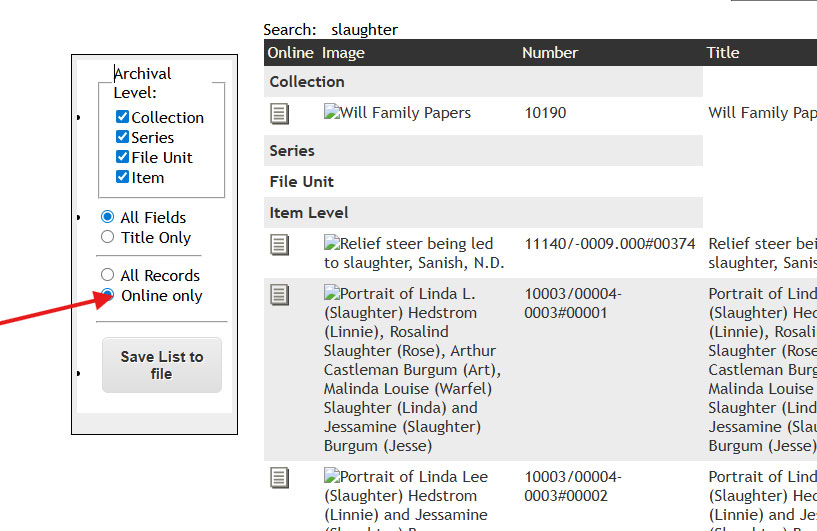

2. How to find scanned items

To determine if something is digitized, begin your search. A global search will include results from State Archives and museum collections and indexes and will order results first by directory, then by archival level.

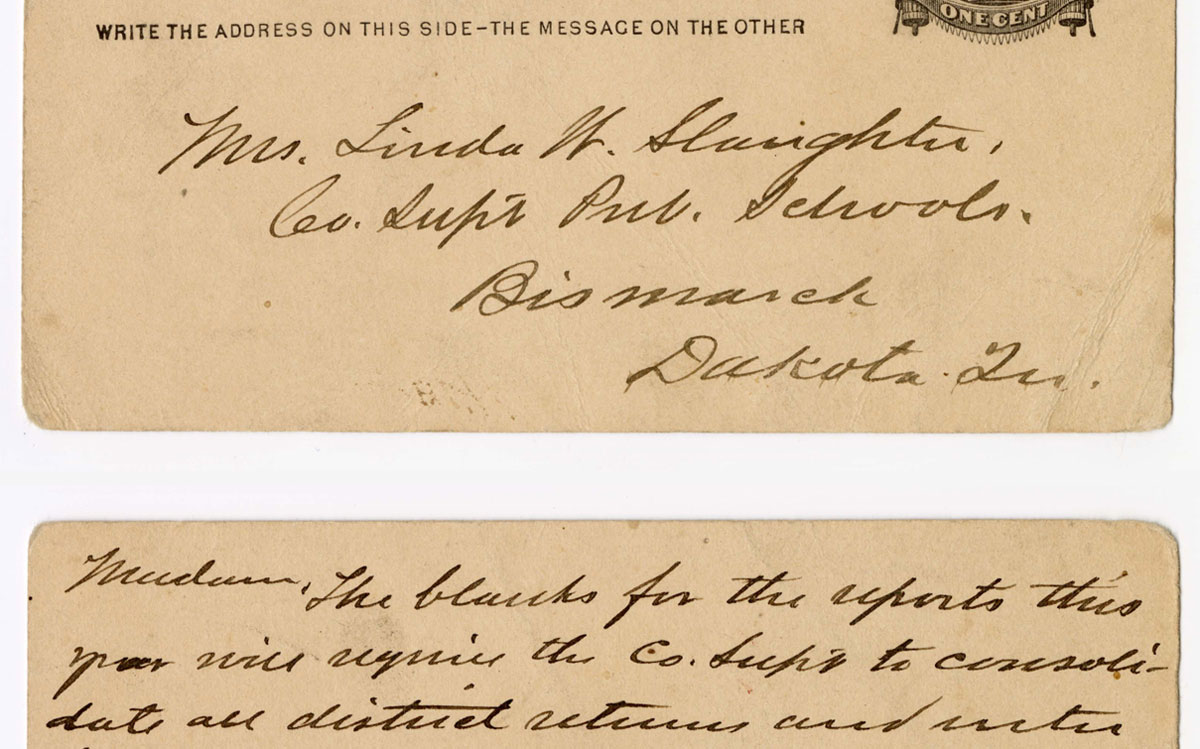

If scanned images are available, they will appear alongside records in the results. Click on the thumbnail to enlarge.

Thumbnails of scanned images appear next to item records in the search results.

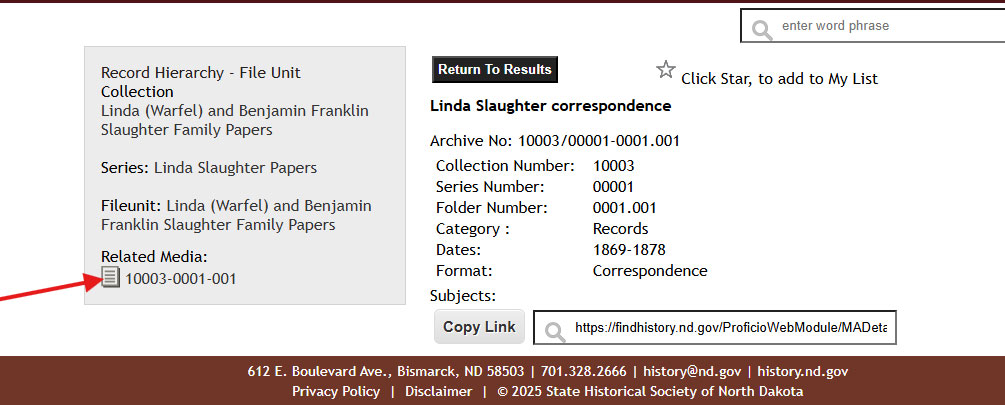

Find available document scans or other media files by clicking into the records.

Then, if documents or other resources have been digitized (into nonimage formats), there will be a file under related media. Click the file name (not the icon) to access the file.

Select the appropriate program to open the file if needed.

Note that a search may be restricted to “online only,” revealing only those results with records or adjacent records (such as collections with at least one digitized item within).

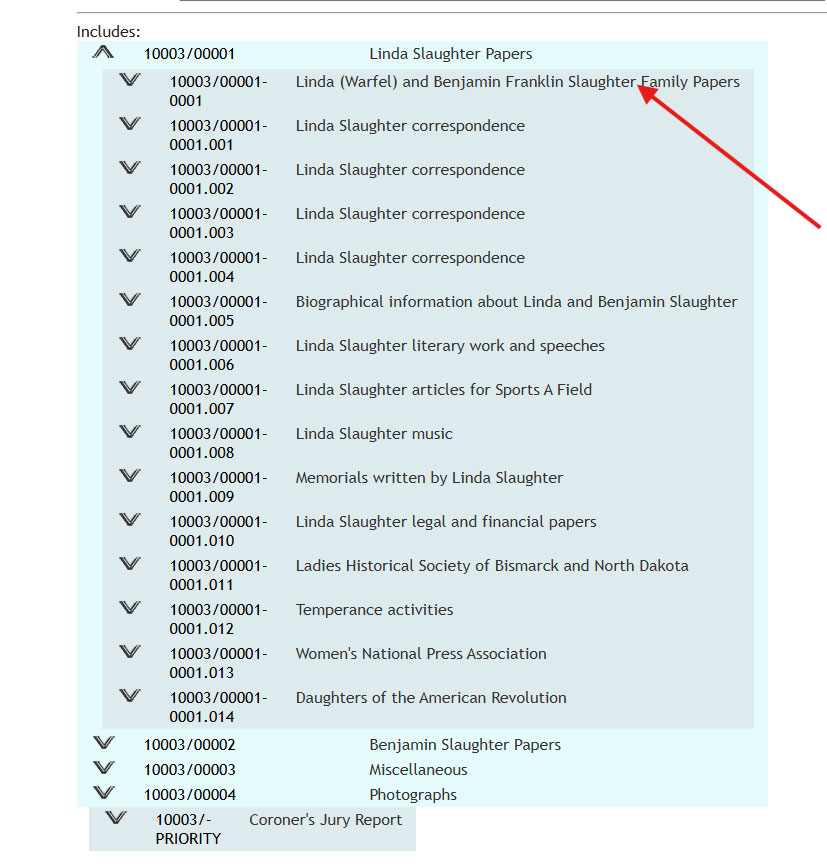

3. View a collection as a whole

To view an entire collection, conduct a global or directory-specific search. You can narrow a search to “collection” for archival level or select a collection level record from global search results by clicking on the collection number. At the bottom of the page, after the collection-level description, there is a section listing the materials in the collection. These might include series, file unit, and item records.

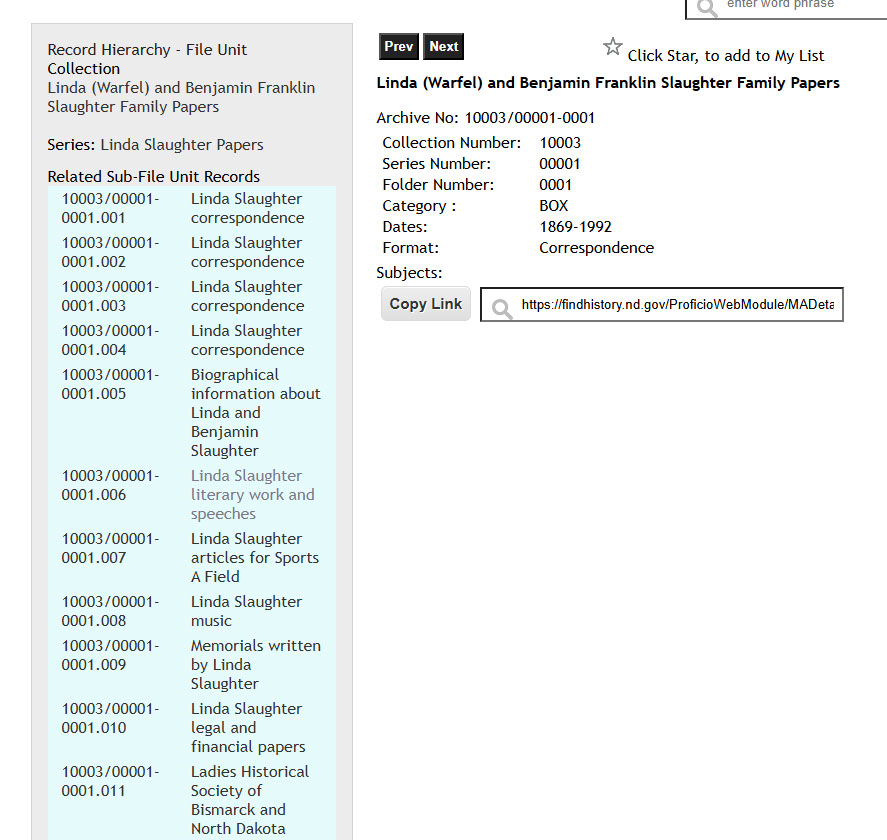

Click on the title of the record for more information.

The right side of the page will describe the selected record. Related records will appear to the left and are searchable.

These three tips for searching fiNDhistory are a great starting point. Additional tips for navigating the site can be found on this YouTube video. If you have any questions or need assistance, we are happy to help! Contact us at archives@nd.gov or 701.328.2091.