For the birds? Budget-friendly Invention Saves Signs and Keeps Our Feathered Friends Happy

Birds have completely domesticated the State Historical Society of North Dakota. No joke, bear with me. I have evidence. To keep our incredible archaeological and state historic sites accessible and attractive to the public, we mow them. Mowing keeps the sites looking tidy, keeps our visitors happy, and lowers the risk of fire. If you have met me and conversed with me in the last year, you may have heard that mowing grass is one of my favorite things to talk about. Never in all the time I was in museum and history school did I learn one single thing about mowing grass—the manpower and expertise needed to do so, the expense of the equipment, or the unintended consequences of mowing.

Agency construction supervisor, fellow Detroit Tigers fan, and turf manager extraordinaire Paul Grahl.

I would like to introduce you to agency Construction Supervisor Paul Grahl. If he didn’t work for the Historical Society Paul might be professionally described as a greenskeeper, turf manager, or groundskeeper. He has numerous licenses and certificates that allow him legal access to a wide range of tools, which he uses to keep our sites looking spectacular. Paul’s responsibilities also include maintaining a vast array of equipment that we use throughout the year. He runs a tight shop; it is neat as a pin, and every tool is in its place. Frankly, it’s beautiful. This time of year, lawn mowers from quite a few of our historic sites show up at Paul’s shop on Main Avenue in Bismarck for regularly scheduled seasonal maintenance. The mowers naturally get put away in preparation for our other season—Plowing Season. Our mow/plow armada includes 17 mowers, five skid steers, one tractor loader, and a forklift.

Two examples from our fleet of 17 mowers.

Now back to the birds and their subjugation of the State Historical Society. Birds love our historic sites. We provide carefully manicured meadows for them to hunt insects and pursue other prey. To help them survey their avian domains, we provide said birds with perfect perches in the form of state historic site interpretive signs. In the bird world, our signs are unparalleled observation points and snacking stations.

One morning this past July, I was at Fort Abercrombie State Historic Site. I arrived there early (the early bird and all) and was fortunate to ride along with Site Supervisor Lenny Krueger as he opened the site for the day. Among his various duties that morning, Lenny washed the bird droppings off the interpretive signs at Fort Abercrombie while I helped sweep out some of the blockhouses. During our ride, I did some quick “Bill math” that entailed counting our historic sites, adding up interpretive signs, and generally thinking about how much time each historic site’s staff spend per week washing bird poop off interpretive signs. I came up with about $9,500 a year for our role as bird bathroom janitors. That amount seemed like a lot, but it also seemed to me like an unpleasant task that we should try to eliminate. Our interpretive signs are made of high-pressure PVC laminate. If the bird droppings are not removed from signs, they eventually damage signs by fading the colors and causing the first layers of laminate to separate.

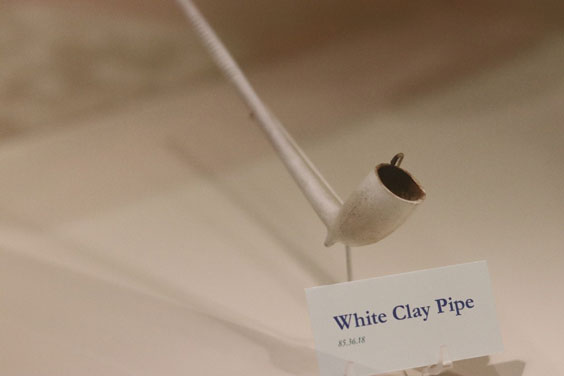

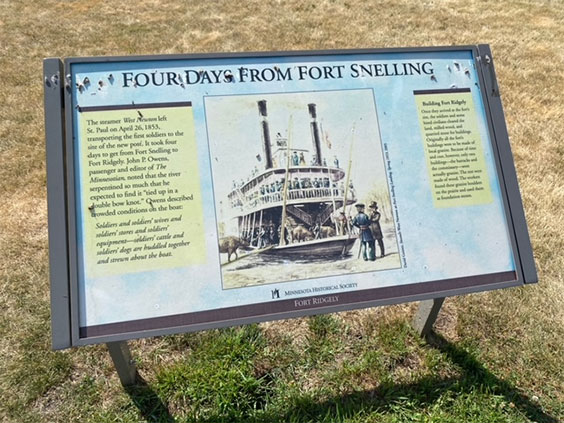

Our friends at the Minnesota Historical Society have the same sign issue. Photo by David Grabistke

Naturally I started to ponder possible solutions. The first round of thoughts involved keeping the birds off our signs. Paul had some good ideas on this topic as well. But here is the thing—I really like birds, and I really like seeing them at our historic sites (except for pigeons, that is a whole different story). So I ruled active deterrents out. I instead settled on ideas that involved improving the signs so birds continue to feel welcome at our sites, saving money, and keeping our signs clean so our staff teams can start each day facing one less unpleasant chore.

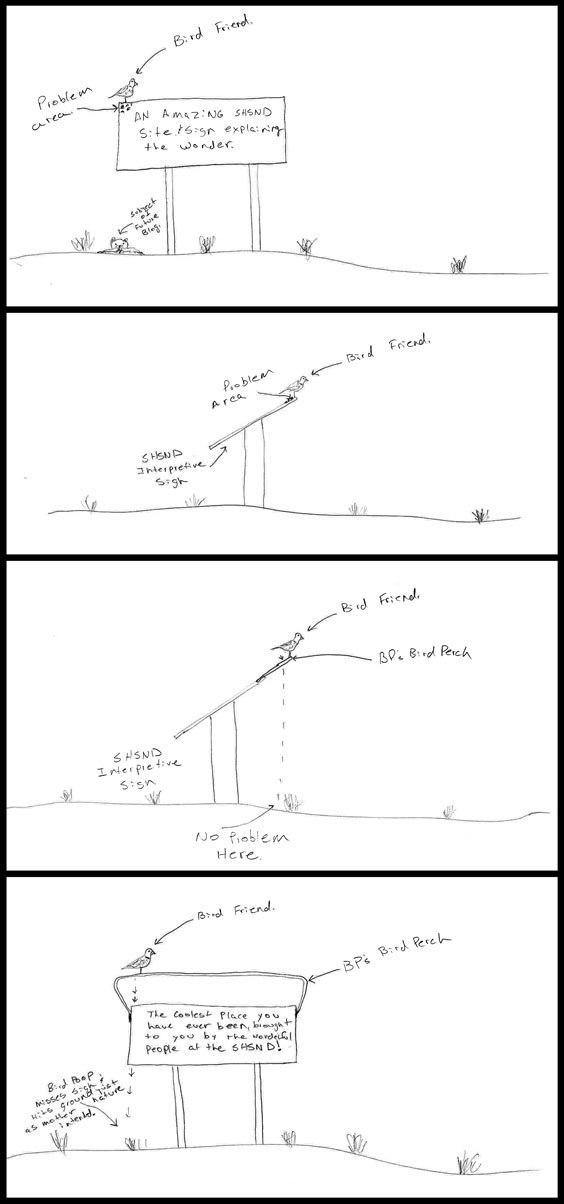

My hand-sketched visual summary of the agency’s avian predicament and revolutionary sign-saving solution.

I am no inventor, but I do love to bang around in the shop. If something is shiny or loud, I am almost guaranteed to love it. After a bit of trial and error, a piece of 5/16 steel rod, a few minutes at the anvil with red hot metal and a cross pein hammer, and six self-tapping sheet metal screws, I came up with a solution of sorts—Bill’s Sign Saver. I proudly showed the prototype to Paul. After he stopped laughing, Paul agreed to install it first at Double Ditch State Historic Site and then at Huff Indian Village State Historic Site. The Huff site is a notorious bird paradise where Paul could quickly collect a lot of data. While the marketing team might have some work to do on the name of the sign saver, early reports indicate we are really onto something when it comes to keeping signs clean. We might make a few more sign savers next summer and collect more data. I’m hoping that we can help other agencies and organizations facing the same challenges with keeping outdoor signs clean and well maintained while continuing to serve our beloved bird visitors.

Paul Grahl test fitting the sign saver in the agency’s maintenance shop.

My sign saver prototype awaits installation.

Bill’s Sign Saver at Double Ditch Indian Village State Historic Site.