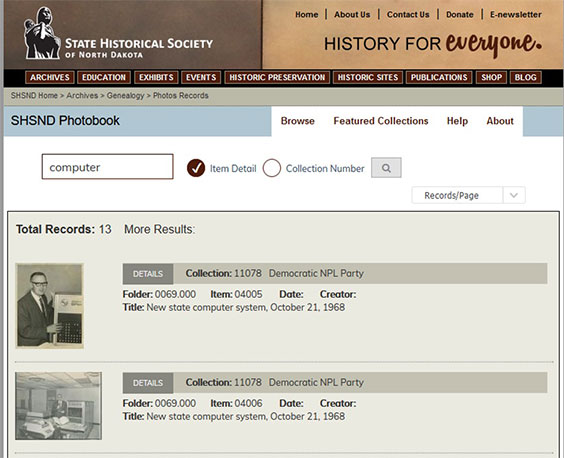

3 “A-ha” Histories Hidden in North Dakota Museum Work: Quirky discoveries about Peggy Lee, Gannon Mystery Murals, and a Tunnel to Nowhere

An impossible ache runs deep when you hold an old document, a childhood toy, or a photograph and connect with its history. It might involve the thrill of finding an unmarked musty dusty box, coming across a long-forgotten love letter, or finding a black-and-white photograph of your hometown. Those moments cause you to pause and sigh with a satisfied “A-ha” as the lines blur between past and present. I’ve been fortunate to experience several of those twinklings in 2020 while working on an upcoming exhibit and new visitor tours. Here are three of my favorites.

1. Mystery Murals in a Hidden Box

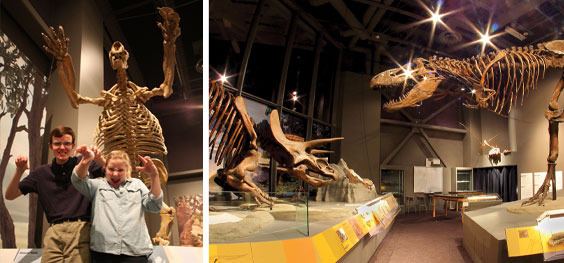

Nothing gets a curator’s heart racing with glee like finding a mysterious box on a storage shelf. The large box was unmarked when a few Audience Engagement & Museum collections staff discovered it. What mysteries would lie within the box? Inside they found 30-some rolled strips of painted canvas with torn edges. As these 10-foot strips were unrolled, my collections team realized these pieces came from State Historical Society murals created as backdrops for 1930s natural history exhibits. Clell Gannon (1900-1962), a regionally known artist and historian, painted the canvases.

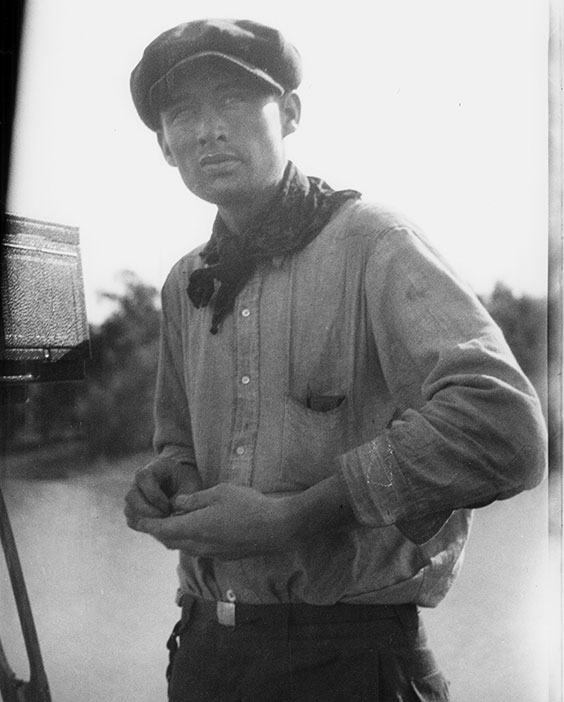

Clell Gannon lived an adventuresome life as a skilled artist, poet, historian, and creator of a charming stone home in Bismarck. You can view a few of his murals at the Burleigh County Courthouse. SHSND 00200-4x5-0402c

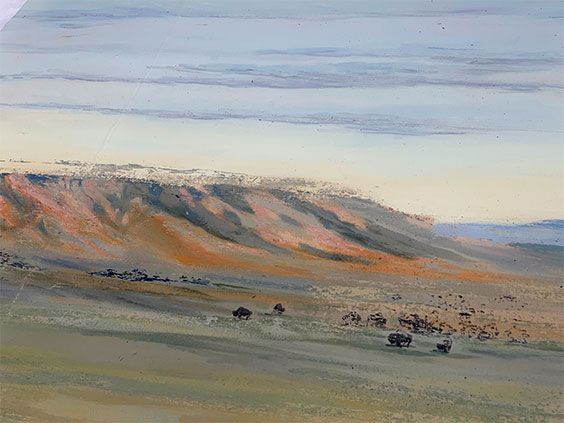

Part of this story remains a history mystery, but we think that Gannon’s North Dakota badlands landscape scenes hung in the Liberty Memorial Building on the Capitol Grounds (now the home of the State Library) until the North Dakota Heritage Center opened on the grounds in 1981. In 1980, the State Historical Society staff moved all museum collections from their space in the Liberty Memorial Building into the North Dakota Heritage Center. The unexplained history mystery evolves around “why” and “who” tore the 13’ x 10’ murals into long narrow strips and placed them in an unidentified box on a shelf.

Deer and antelope shared the exhibit platform in front of artist Clell Gannon’s painted mural at the former State Museum location in the Liberty Memorial Building. SHSND 00200-4x5-C-00402

We’re thrilled about discovering these fragile murals and are in the process of digitally bringing Gannon’s artwork back to life. In June, while the State Museum was closed due to COVID-19, we opened the box while we had daily access to sparkling clean and empty museum corridors. Our curators carefully unrolled each 90-year-old strip on long tables and gently brushed off areas of flaking paint. All the strips have deteriorated, but oh my, they are still beautiful. Gannon’s bison—blurred from peeling paint—represent a former generation of these majestic herds that continue to thrive in the badlands today.

David Newell, Jenny Yearous, and Lori Nohner of the Audience Engagement & Museum team unroll and prepare a section of a Clell Gannon mural for photographs.

Loose paint flecks are carefully removed from the panels by Jenny and Lori, one small brushstroke at a time.

New Media Specialist DeAnne Billings begins photographing two adjacent strips of a mural. Similar to a quilter, she’ll digitally stitch the pieces together to create two murals.

Over the next several months, DeAnne will be digitally “stitching” the sections of these two murals back together, like a careful repair of a beloved old quilt. Watch for our 2021 digital reveal of these artistic treasures.

Here’s a sneak peek at a few of Clell Gannon’s badlands bison on small section of a mural, painted about 90 years ago.

2. Peggy Lee’s Hidden Talent Trove

Like one of Grandma’s quilts tucked into a dusty attic trunk, famous Wimbledon native Peggy Lee’s fashion designing talents were hidden away. Familiar with Disney’s classic “Lady and the Tramp” film? Then you already know Peggy Lee’s trademark sultry purr. She’s the voice of both Siamese cats, Peg, and Darling. The talented Lee also composed and sang three of the movie’s memorable songs (“He’s a tramp, but I love him...”). Or you might know her from her many #1 Billboard hits such as “Fever.” What you might not be aware of is this North Dakota native’s lesser known artistic talent.

The “Lady and the Tramp” film (one of my all-time favorites!) showcases the multifaceted brilliance of Peggy Lee. She helped compose the score, sang songs, and was the voiceover of four characters including Peg. Did you know “Peg” was named in tribute to her? Credit: © Walt Disney Productions

Peggy Lee was considered a celebrity fashionista of her day, often appearing on stage in gorgeous form-fitting gowns. Over the years, I’ve wondered where she purchased her stunning wardrobe. Where does a North Dakota girl shop after she becomes internationally famous? Which designer’s label was her go-to?

While recently researching and writing about Peggy Lee for an upcoming fashion exhibit, I had an opportunity to speak with Lee’s granddaughter Holly Foster Wells. Of course, I had to ask about the gowns. Wells shared, “After she became famous, my grandmother used to sketch all of her gowns. She designed her gowns and had a seamstress who made clothes for her come to her house every day. She was very into fashion.”

From bathrobes to ball gowns, this Theodore Roosevelt Rough Rider Award winner designed most of her own stylish garments. I love learning another dimension to Peggy’s amazing talents—Grammy award-winning singer, composer, and actor by day, and talented clothing designer at night.

“Her wonderful talent should be studied by all vocalists; her regal presence is pure elegance and charm,” Frank Sinatra once said about Peggy Lee. You can view one of Peggy Lee’s early performance dresses in our Fashion & Function: North Dakota Style exhibit opening at the State Museum in Bismarck in January 2021.

3. Rumors of a Hidden Tunnel to Nowhere

About 20 steps from my office at the ND Heritage Center & State Museum is a non-descript, ivory metal door--always locked. Behind this door is a short tunnel, winding around a couple of turns and abruptly ending with a stark cement wall after 79 feet. So what’s the story behind this quirky hidden tunnel?

What’s behind this locked door at the North Dakota Heritage Center & State Museum?

As a high school student when the ND Heritage Center opened in 1981, I remember hearing rumors about a newly constructed tunnel system running underneath the State Capitol. As the rumor went, it was allegedly a secret emergency escape route for the governor. While “The Case of The Secret Escape Tunnel” might have caused Nancy Drew and her gal pals Bess and George to come running, alas, the rumor isn’t true. The real story, however, is a noteworthy piece of North Dakota government’s architectural planning history.

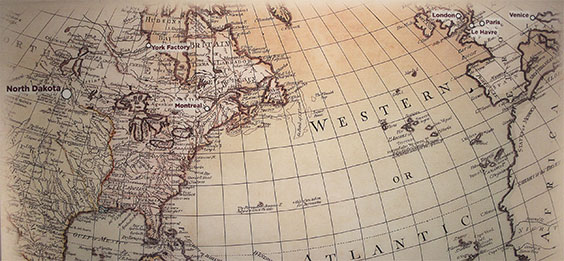

Here’s the scoop: This tiny tunnel was part of the original ND Heritage Center construction project. The architectural plan included an underground passageway connecting this building with the Department of Transportation (DOT) building and the State Capitol, all located within eyesight of each other. If completed, the service tunnels would have been used by state employees for easy multi-building access. An underground walkway between the Capitol and DOT was constructed and is currently used by staff, but at the ND Heritage Center, only our small concrete segment of the tunnel was started. Lack of funding stopped the project. Your challenge: Try to find the door to the “hidden tunnel” during your next trip to the ND Heritage Center & State Museum! It’s hidden in plain view.

No physical distancing is needed in the North Dakota Heritage Center’s tunnel to nowhere. This cement wall is the end of the journey.

COVID-19 concerns have caused our team to shift several professional priorities in 2020, providing an unusual invitation for us to look deeper into some hidden places. While living the sobering realities and challenges of a pandemic in our personal and professional lives, our Audience Engagement & Museum team continues to create positive, engaging visitor experiences for the citizens of North Dakota, retaining a sense of wonder as history continues to reveal itself in our work.