Why I Believe in Historic Sites Tourism

When I was a kid growing up in North Dakota, I didn’t get to travel much, but I dreamed of going to Europe and seeing its historic sites and cities. So you can imagine my delight when, as a grad student, I got to move to Germany for a few years and visit Paris, London, Florence, and even less-traveled places like Bulgaria and Cyprus. This led me to reflect on historic sites, both in Europe and at home, and how their popularity often has more to do with location than significance. In particular, I came to appreciate the historic places I knew and loved back home. Childhood me could never have guessed that I would get to live in a 16th-century German half-timbered house, but while there I also yearned to be back at On-a-Slant Village in Mandan. To my own surprise, I found myself trying to remember exactly how the prairie grasses smelled there when their scent was carried on the springtime wind.

St. Olav’s Church, a beautiful building I first learned about on a visit to Tallinn, Estonia, in 2010, may have been the world’s tallest building in the late 1500s to early 1600s. It taught me that often the fame of a historic site has more to do with its location than its actual merits.

Like so much else in this world, people give too much attention to just a few things. Just as there are celebrities among people, there are celebrities among places. It leads to a serious imbalance in global tourism. I’m just one of millions of people who want to—and do—visit Tuscany, the Rhein Valley, and so forth. But these incredible numbers of visitors are doing lasting harm to hotspots like Venice, Florence, Amsterdam, New Orleans, and Yellowstone. Meanwhile, North Dakota remains the least-visited state in the United States.

A healthy number of interested tourists incentivizes locals to preserve their historic places, as well as the music, art, languages, food, architecture, and landscape that go with them. The incentives may be financial. At the Etâr Ethnographic Open Air Museum in Bulgaria, for example (highly recommended, by the way), people are hired to make traditional arts and crafts, many of which are also sold to visitors. The incentives may also simply be inspirational—seeing visitors’ excitement reminds locals of the value of their own heritage. Frankfurt, Germany, for example, which receives moderate visitation, recently reconstructed several streets of their historic old town that had been destroyed in World War II.

The world’s superstar attractions need fewer visitors, while places like North Dakota need more. Last December, the Netherlands announced a rebranding effort aimed in part at attracting fewer but higher-quality tourists. Maybe someday we’ll convince them to sponsor Travel ND ads to lure some visitors away from them and toward us!

Over 15 summers working at various historic sites in North Dakota, I’ve been fortunate to meet thousands of tourists, and I’m happy to report that they’re exactly the kind of visitors the Netherlands dreams of. Because North Dakota is far away from major population centers and transportation routes, those who come here do so with intention. They ask thoughtful questions and want to enjoy everything North Dakota has to offer.

You’d be shocked to learn, however, how many only came here because they want to visit all 50 states, and usually I hear that this is their last one. Sadly, most hadn’t heard what’s unique about North Dakota—things that might attract many more people. Just some examples:

- Traditional dishes like rØmmegrØt, knoephla, wojape, and the taste bud-defying lutefisk.

Comfort food for North Dakotans may be a memorable cultural experience for visitors. This knoepfle soup was made for a special event by the Road Hawg Café in Hazelton.

- Dozens of unique corn varietals with different flavors bred over centuries by North Dakota tribes.

- Earthlodges—an American Indian style of architecture uniquely adapted to the Plains.

- Radio in French or Native American languages that can still be heard in different parts of the state.

- This is the original homeland of the tipi, or that their familiar shapes are actually a masterpiece of thermodynamics.

- The corners of the state, being in the middle of North America, resemble microcosms of the continent, such as yucca and prickly pear in the southwest Badlands to aspen and birch forests in Pembina County.

- The unique Métis nation that arose from the Red River fur trade.

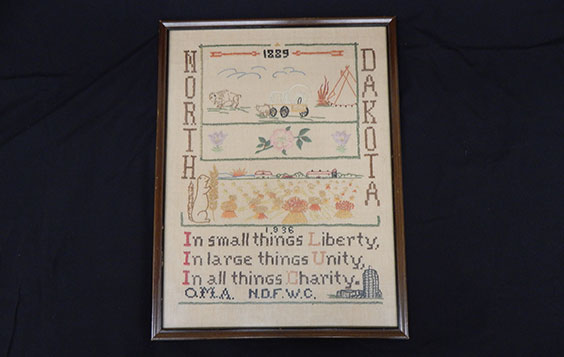

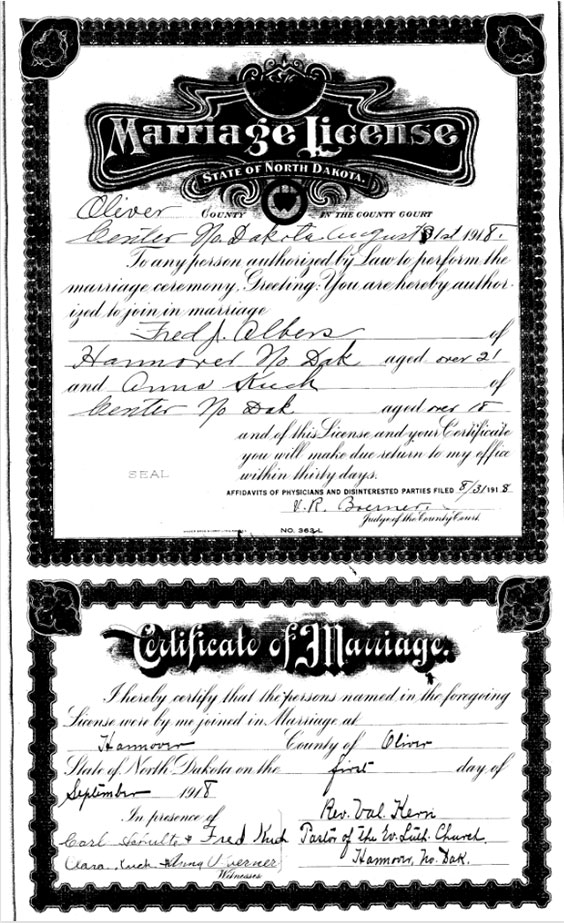

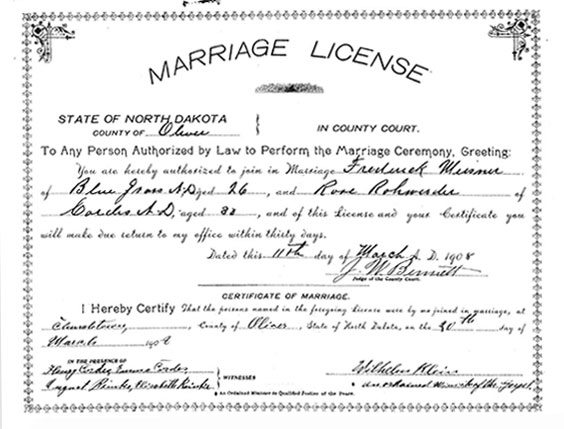

- Many North Dakota towns beginning as settlement colonies of a specific village in Europe, each mirroring the dialect, religion, and family names of its mother village in the old country.

- North Dakota’s unique state-owned grain elevator, selling popular flour, bread mix, and pancake mix you can buy at most grocery stores.

- Games like Dakota and Arikara doubleball or German-Russian horse knucklebones (bunnock), which are as entertaining to watch or play as any modern sport.

- Lakota winter counts that preserve tribal historic records stretching back long before European contact.

- Stunning fields of flax, sunflowers, and canola in bloom.

- Coal mines where you can visit the pit and see the actual wood grain of ancient jungles preserved in lignite.

But when I share these things, they’re almost always fascinated and want to learn more. Many only planned to spend a day in North Dakota and told me they wished they had known to plan more time.

Historic sites both attract these visitors and share this culture. You can’t (and shouldn’t) walk into a modern German-Russian or Mandan home, but you can visit Welk Homestead or Double Ditch Indian Village. We can and do share the music, stories, food, clothing, and games of North Dakota’s unique heritage, being careful, of course, not to misuse culture that is sacred or proprietary. We are delighted to direct visitors to the families, communities, businesses, and tribes who know this culture best. That’s how sustainable tourism works.

This work is urgent. Since I started working at North Dakota historic sites in 2005, it has become harder and harder to find artists, artisans, language speakers, and other cultural experts who can recreate a historical object for us or appear as a guest speaker. Many have passed away before the next generation recognized the value of what they knew. It would be amazing if many more North Dakotans could make a career teaching Lakota, forging German-Russian cemetery crosses, serving potato klubb, making birch baskets, weaving Métis sashes, and more.

North Dakota has all the culture it needs to rival Boston, Santa Fe, or Albuquerque. It’s not so wild a dream. New Mexico at the end of World War II was even more remote than North Dakota, yet they preserved or rebuilt their historic structures, carried on their cultural traditions, and made the rest of the world aware of how many unique things they had to see and do. That’s the vision that I and many other North Dakotans who love historic places see. Let’s work towards balance. Let’s give people a reason to give touristy cities a break and come visit us. We’d be doing everyone a favor.