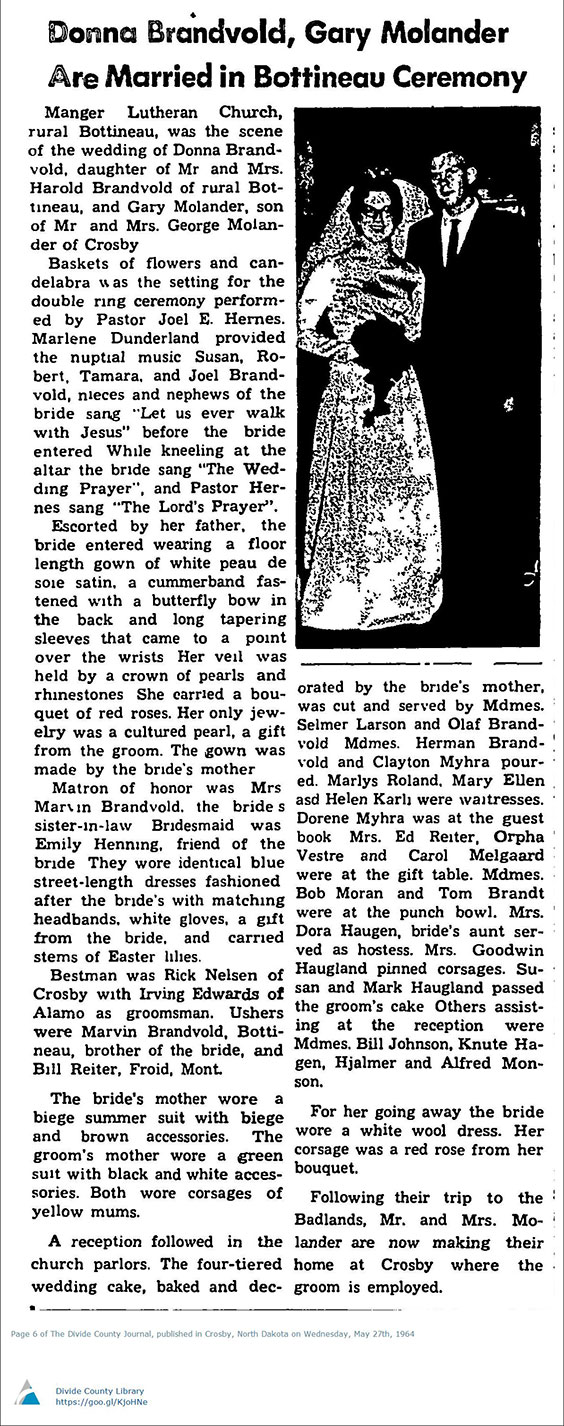

AmeriCorps Volunteers Help Out at Fort Totten

On September 15, 2018, a team of AmeriCorps volunteers arrived at Fort Totten State Historic Site. The team, comprising eight volunteers aged 19 to 25, originated from all over the United States. Tasked with cleaning out the historic gymnasium in preparation for restoration, the team members got to work almost immediately.

AmeriCorps team members upon arrival, posing in the auditorium at Fort Totten State Historic Site.

Created in 1993, AmeriCorps is a federally funded volunteer program that sends teams all over America to complete their mission of “helping others and meeting critical needs in the community.” The process of acquiring an AmeriCorps grant and team began back in 2016 with several meetings between State Historical Society staff and AmeriCorps leaders. Upon acceptance, the staff of Fort Totten began preparations for the team’s arrival. The team would be staying at the Totten Trail Historic Inn, a Victorian-themed bed and breakfast operated by the Fort Totten State Historic Site Foundation and housed in the former Officer’s Quarters on the grounds of Fort Totten State Historic Site. Accustomed to sleeping outside and in church basements, the team rejoiced at having their own bedrooms and bathrooms for the duration of their visit.

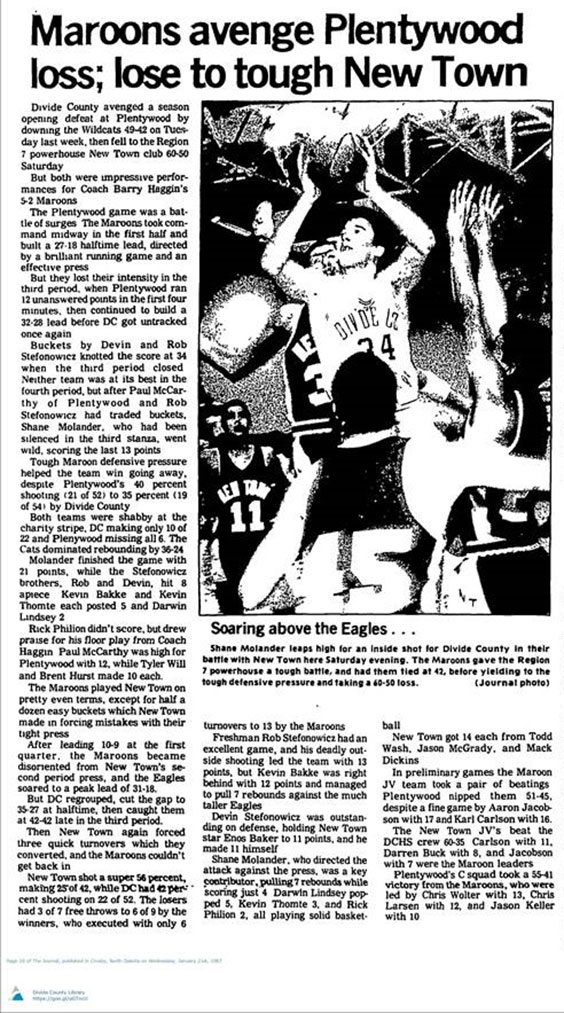

Team members pose outside the gymnasium during clean-up.

Fort Totten staff slated 2-3 weeks for the gymnasium cleanup and were amazed when the project was completed in just five days. The team members then moved onto a lengthier project — the rehousing of the museum collections of the Lake Region Pioneer Daughters. You may remember from my previous blogs that the State Historical Society has made the restoration of the historic hospital/cafeteria a priority in the last few years. The historic hospital/cafeteria at Fort Totten has been home to the Lake Region Pioneer Daughters and their collections since 1960. Since the massive overhaul and restoration of the building, completed in 2017, the collections were housed in boxes throughout the basement of the building and accompanying buildings. AmeriCorps was tasked with combining the collections from multiple buildings, removing the objects from unsatisfactory boxes and housing, placing them in archival, acid-free boxes, and adding object tags with accession numbers to the items and boxes. Team members spent almost three weeks working on this project and were fascinated by the many treasures discovered in the vast collections.

Americorps team members rehouse the Lake Region Pioneer Daughters collection in the historic hospital/cafeteria at Fort Totten State Historic Site.

The experience of working with AmeriCorps was phenomenal and one we hope to have again. The young people involved were truly committed to public service and strengthening communities. We’re very excited to see what becomes of these young people and what they choose to do with their lives after AmeriCorps.