Top 5 Most Fascinating World War I Artifacts in the State Historical Society Collection

One of the things I love most about my job is that I get to work with a truly world class collection. It is the product of over a century of collecting, and with nearly 74,000 artifacts, it never ceases to surprise me. We have lots of things that are just downright fascinating to me, not because of what they are, but because of what they represent and what they speak to. Items that give a human touch to an event or time period, or that give us an idea of what it was like to be there.

Our collection of World War I artifacts is rich with such items. The State Historical Society collected extensively during the war, bringing in artifacts from both individuals and from the US Government. I’d like to share my list of the top 5 most fascinating World War I artifacts, all items that will be on display in the Sperry Gallery at the North Dakota Heritage Center & State Museum starting in August.

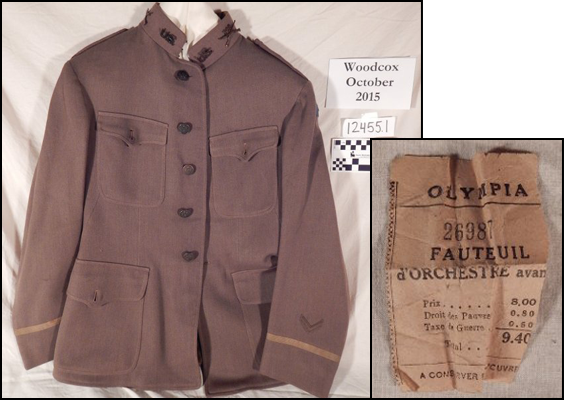

1. Orchestra Ticket and US Army Uniform Jacket (12455.1, 12455.3)

I recently completed a major project with our military uniform collection. I quickly learned to check the pockets of uniforms, because I started finding surprises. One of the best was an orchestra ticket from France crumpled into the breast pocket of a uniform jacket, like it had been forgotten there. What makes it fascinating to me? The last person to touch that ticket was probably the man who wore the uniform, and it may have even been when he was still in France. There is no way to know. It’s a very human thing to do, to forget things in your pockets, and it makes the artifact more personal to me.

2. French Combat Helmet with Battle Damage (1990.142.4)

This French combat helmet, like many of our World War I artifacts, was sent to us directly from the battlefields of France by Major Dana Wright, a North Dakota soldier. What makes it unique is the actual battle damage—an entry hole from a bullet on the right side and an exit hole on the right front side. We don’t know how the helmet came into Major Wright’s possession, and we have no way of knowing if the French soldier who wore it survived, but it speaks firsthand to the conditions and dangers of World War I battlefields.

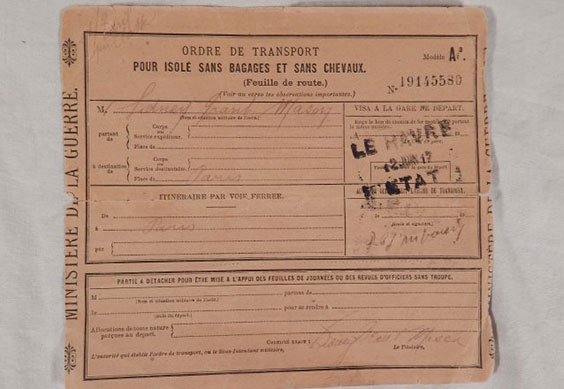

3. French Army Leave Slip (L815)

A resident of Fargo, Sydney Mason joined the French Army and served on the battlefields in the Ambulance Corps. In June 1917, he was granted leave to visit Paris. According to the pass, he was not allowed to carry luggage or take a horse. It fascinates me for two reasons: for one, I didn’t know that Americans joined the French Army during the war prior to seeing this. Also, how many of these documents actually survive? It is something that would commonly be disposed of after it was used, and many probably met that fate.

4. German Mourning Card (L92)

This mourning card was found in a German trench by a (then) private named Neil Reid, who was part of an American unit that had just pushed the Germans back. It was sent to his mother in North Dakota, who then loaned it to the State Historical Society. The card memorializes a 20- -year-old-German soldier killed in April 1918 named Peter Rappl. Was he a loved one of a soldier who had just retreated? These were often handed out to the families of fallen soldiers, but it is a question we can’t answer.

5. German Combat Helmet (1990.142.3)

We have 18 German combat helmets in the collection and 22 dress helmets, making them far from rare. What makes this one unique? It was mailed to us directly from the Meuse Argonne Sector in France after being picked up on a battlefield there. I don’t mean that it was placed in a box and shipped to us—three 12-cent postage stamps and an address label were stuck to the side of the helmet. The label, which you can see in the photo above, is still attached. Unfortunately the postage stamps were removed at some point in the last 100 years. I’ve heard you can mail almost anything as long as it has enough postage, but who knew you could drop a helmet in the mail and have it delivered?

You can see all of these items and many more in our World War I exhibit, which will be opening in August.