Revisiting Old Collections: Native American Pottery from the Jennie Graner Site

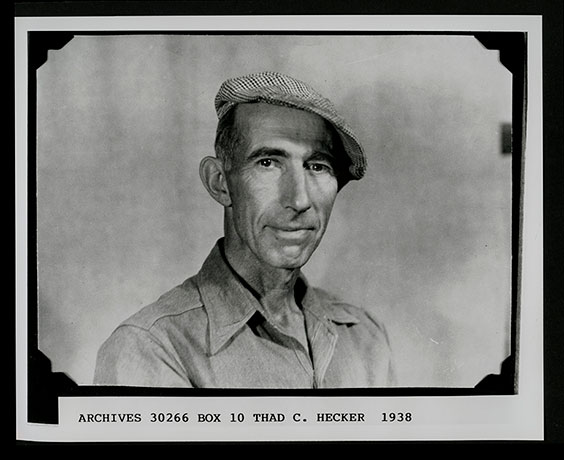

The most interesting discoveries an archaeologist can make occasionally involve artifacts collected decades earlier. I happened upon such a discovery while preparing to carry out fieldwork on behalf of a federal agency. While conducting background research, I learned the State Historical Society houses a small ceramic assemblage originally collected in 1938. These 73 ceramic rims and body sherds represent the bulk of artifacts collected from site 32MO12, or the Jennie Graner site. My search for information about the pottery itself, as well as the history of previous research at the site, led me on a winding path through archival records and the handwritten notes of Thaddeus C. Hecker, a former archaeologist with the State Historical Society.

Hecker is probably most well-known to archaeologists who have read his and George Will’s inventory of Plains Village sites along the Missouri River in North Dakota1. Previous to this 1944 publication, Hecker and other archaeologists working for the state identified a Plains Village site on the west bank of the Missouri River near the town of Huff. At that time, the site was on the property of Jennie Graner and was named after her. Although Hecker collected pottery in 1938, there is no indication that he conducted excavations at the site:

The first time I visited this site I found a lodge floor in the cut-bank where an unusual amount of pottery of various designs in decoration had weathered out. The rim-sherds were rather thick and all decorations were punch incised; also a number of designs in decoration were different than I had seen before…The pottery of this site is undoubtedly of Mandan Culture.2

Thaddeus C. Hecker, 1938. (State Historical Society of North Dakota C3717-00001)

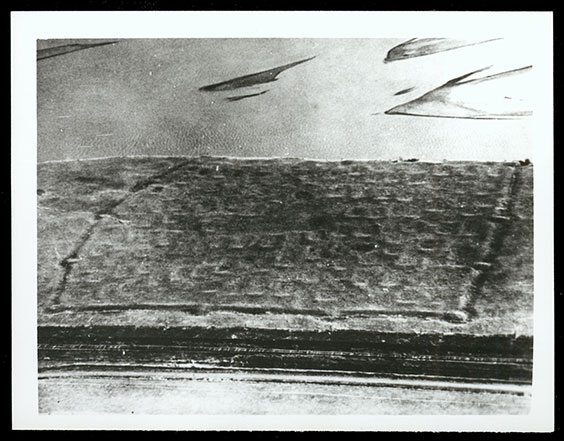

Although Jennie Graner is considered an earthlodge village site, no remnants of earthlodges or middens are visible on the surface like they are at other Mandan sites such as Huff and Double Ditch villages. There is also no evidence of a palisade or ditch at Jennie Graner. Perhaps the Mandans who lived there did not need a protective wall around their village—or perhaps evidence of lodges and ditches have been obliterated by farming and construction activities. Even in 1944, Will and Hecker reported that the site was eroding into the river and was severely impacted by modern earthmoving activities.

Aerial view of Huff Village State Historic Site, located south of the Jennie Graner site. Note earthlodge depressions and fortification ditch. (State Historical Society of North Dakota 00630-04)

The age of the Jennie Graner site is unknown, but Will and Hecker referred to it as “Archaic Mandan,” or what archaeologists now call the Extended Middle Missouri. The latest regional chronology of village sites gives the Extended Middle Missouri an age range of AD 1200-14003. Ceramic analysis suggests Jennie Graner would fall toward the end of this age range, possibly in the late 1300s or early 1400s. Pottery styles and designs changed through time, but these changes did not happen overnight. New styles were tested and incorporated slowly, resulting in many ceramic forms occurring contemporaneously. Four types of ceramic “ware” have been identified from this site. The earliest wares are Riggs ware and Fort Yates ware. These are followed chronologically by Stanton ware and Sanger ware, respectively4. Riggs and Stanton wares have straight rims, while Fort Yates and Sanger wares have S-rims. The presence of transitional forms between Riggs and Stanton, and between Fort Yates and Sanger, suggests potters at Jennie Graner may have been experimenting with vessel construction and decoration.

Left: (a) Riggs ware rim. Note the tall rim and location of tool impressions directly on the lip; (b) Transitional form between Riggs and Stanton wares. Rim height is shorter, and tool impressions appear lower on the rim; (c) Stanton ware rim. Addition of fillet with tool impressions well below the lip of the rim. (All specimens SHSND 7123)

Right: (a) Fort Yates ware rim. The juncture of the rim and neck is angular; (b) Transitional form between Fort Yates and Sanger wares. The juncture is less angular and becoming more curved; (c) Sanger ware rim. The juncture between the rim and neck is curved. (All specimens SHSND 7123)

Jennie Graner is on land managed by the US Army Corps of Engineers. Recent testing of the site by State Historical Society archaeologists will tell us more about the size, age, and occupation length of the village, as well as whether it qualifies to be nominated to the National Register of Historic Places. We also hope to learn its relationship to the nearby Huff Indian Village State Historic Site and other Missouri River Mandan villages.

1 Will, George F. and Thad C. Hecker. 1944. The Upper Missouri River Valley Aboriginal Culture in North Dakota. North Dakota Historical Quarterly, vol. 11 (1-2), pp. 5-126.

2 Hecker, Thad C. 1938. Morton County Archeology. Manuscript on file at the State Historical Society of North Dakota, Archaeology & Historic Preservation Division.

3 Johnson, Craig M. 2007. A Chronology of Middle Missouri Plains Village Sites. Contributions to Anthropology 47. Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press, Washington, D.C.

4 Ahler, Stanley A. 2001. Analysis of Curated Plains Village Artifact Collections from the Heart, Knife, and Cannonball Regions, North Dakota. Research Contribution No. 42, PaleoCultural Research Group, Flagstaff, AZ. Submitted to the State Historical Society of North Dakota.