12,000 Years, A Piece of Flint, and a New Pursuit

Number “22” launched me into the world of archaeology.

Let me explain.

It was Sunday, July 30, 2006, day #7 of a nine-day archaeological project at a place called Beacon Island in northwestern North Dakota.

In those seven days, I had progressed to the point where I was trusted with a trowel, a kneeling pad and my very own archaeological “unit.” The unit was my very own 1 meter by 1 meter square of potential discovery.

It had been very hot, 112 degrees a couple of days before, and just about the same that Sunday afternoon. It was an exciting week but the heat, the baloney sandwiches, and the lack of a long shower was beginning to take a toll on my enthusiasm.

About 2:30 that afternoon, the very distinct sound of metal hitting stone resonated in my sunburned brain. I quickly realized that the sound didn’t come from my trowel, but from the unit immediately to my left. A University of Chicago field school student had discovered a piece of Knife River Flint that would fuel my imagination.

Beacon Island was the site of a brief (one-or two-day) event that took place roughly 12,000 years prior to that hot Sunday afternoon. I wrote of Beacon Island in one of my previous blogs so I won’t retell the entire story. In short, a band of Paleoindian hunters surrounded a herd of twenty-nine or so Bison antiquus, killed them, butchered them, cooked some of the meat, prepared some of the rest for transport, sharpened their tools, and moved on.

Something they left behind that day would, 12,000 years later, become number “22.”

After the completion of the project, the PaleoCultural Research Group (PCRG) issued the official report of the Beacon Island survey. The 275-page report detailed every aspect of the study. On page 144 of the report, the following appears:

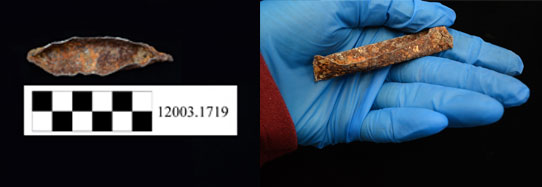

“All but one of the projectile points from Beacon Island are morphologically and technologically consistent with points from the Hell Gap and Agate Basin sites…The lone exception is the base of what can be called a Goshen point…This specimen is made from KRF (Knife River Flint) and is relatively broad and flat…Given its position in the bone bed there is no doubt that this point was among the weapons used in the kill.”[1]

The flint projectile point “…was among the weapons used in the kill,” and I was the second person in 12,000 years to view it “in situ” at Beacon Island.

I followed the Goshen[2] point, along with the rest of the artifacts uncovered during the project, to the archaeology lab at the State Historical Society of North Dakota (SHSND.) I, along with other volunteers, spent the winter of 2006-2007 sorting and consolidating the bone, stone, shell, pottery and other material from Beacon Island. By that time, I was firmly hooked on the archaeology of North Dakota.

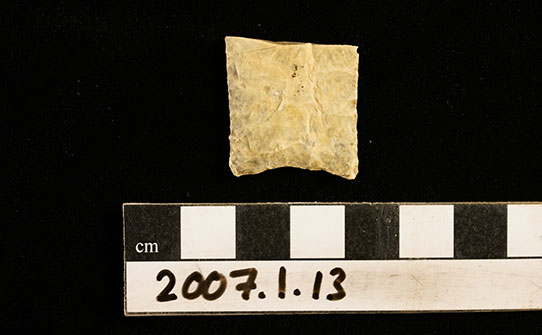

The little Knife River Flint projectile point discovered that hot July day disappeared into the artifact collections of the SHSND for a couple of years, awaiting its designated spot in the display cases of the Innovation Gallery: Early Peoples at the North Dakota Heritage Center & State Museum. It had been photographed, assigned a museum catalog number (2007.1.13), and packed away, ready to become a part of the permanent Beacon Island exhibit.

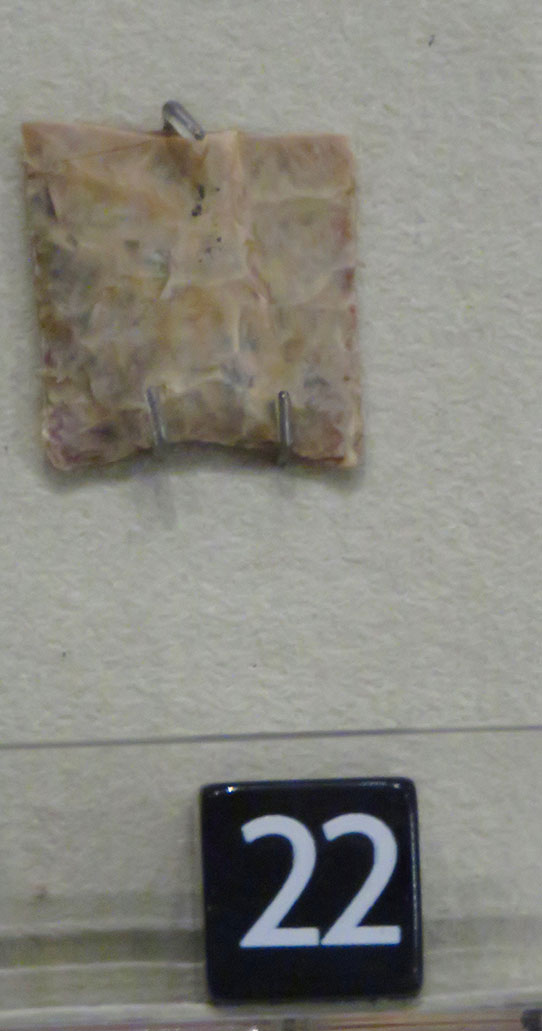

The Goshen point reappeared in 2014, identified as number “22” in the glass Beacon Island exhibit case.

Since the discovery of number “22,” I have had the opportunity to volunteer on a number of North Dakota archaeological projects and serve as president of the North Dakota Archaeological Association. Each project is unique and brings to light a variety of interesting artifacts, each with its own story. None, though, hold the personal fascination for me that little number “22” holds.

Since the discovery of number “22,” I have had the opportunity to volunteer on a number of North Dakota archaeological projects and serve as president of the North Dakota Archaeological Association. Each project is unique and brings to light a variety of interesting artifacts, each with its own story. None, though, hold the personal fascination for me that little number “22” holds.

I stop and visit number “22” every time I am in the Early Peoples gallery. I still get a couple of goosebumps, mixed with a little nostalgia, every time I view it. It will always be “my” artifact, the little piece of Knife River Flint that got me involved in and fascinated with the field of archaeology, and which links me to a fellow human being 12,000 years in the past.

Stop by and see number “22” for yourself when you visit the North Dakota Heritage Center & State Museum. Let it tell you the story of the 12,000 years between the time it was used to kill a Bison antiquus until it reappeared at the hands of an archaeology student at Beacon Island and opened a new field of study for me.

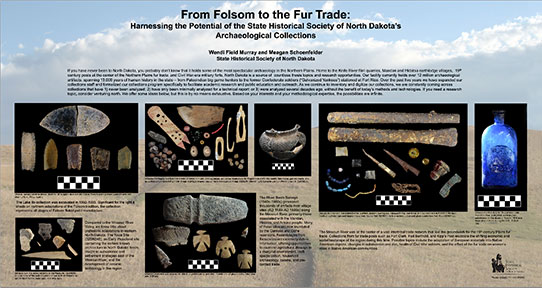

Learn more about Beacon Island in "From the Field to the Museum." This video is part of the Making Archaeology Public Project, which was created to honor the 50th Anniversary of the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966.