Getting to Know Star Village

I was doing some research on Arikara settlement the other day, and started going through our flat files. Our flat files contain many of the large archaeological site maps and photo plates that we have accumulated since we became an agency. Many of them, such as maps by archaeologists E.R. Steinbrueck and A.B. Stout, are some of the oldest maps we have of earthlodge villages along the Missouri River. I turned to this collection because I wanted to see what A.B. Stout had written in his notes about Star Village, the village that the Arikara people occupied before they moved to Like-A-Fishhook Village in 1862.

Our division’s flat files, containing oversized site maps, photo plates, aerial photos, plan maps, etc. It is a good thing that I love going through these files, because one of my responsibilities this year will be to digitize, scan, and organize this whole collection.

I should note that Stout didn’t stick with archaeology – he actually ended up moving to New York and becoming a renowned botanist, best known for his expertise in plant genetics (specifically, the hybridization of daylilies). But before he became a leading plant scientist, he worked for our agency mapping and excavating village sites.

My research focuses on the settlement of the Arikara people at Like-A-Fishhook. A few weeks ago, I was agonizing over the function of log cabins mapped at that village – some of them seemed like they might be dwellings, but others were too small, too compartmentalized, or attached to an existing earthlodge. Could some of them have been used to stable horses? Or maybe some were used as storage annexes? Normally, an archaeologist could look for answers by excavating these features at the site. But that is not an option for me. For some reason, most of the research questions I am passionate about revolve around sites that were permanently inundated in the 1950s by Lake Sakakawea. I realize that this is not ideal. Am I a glutton for punishment? Maybe. But I am also a collections manager, and believe that with some creativity (with approach, questions, and methods), paper records and artifact collections still have much to tell us about sites we no longer have access to.

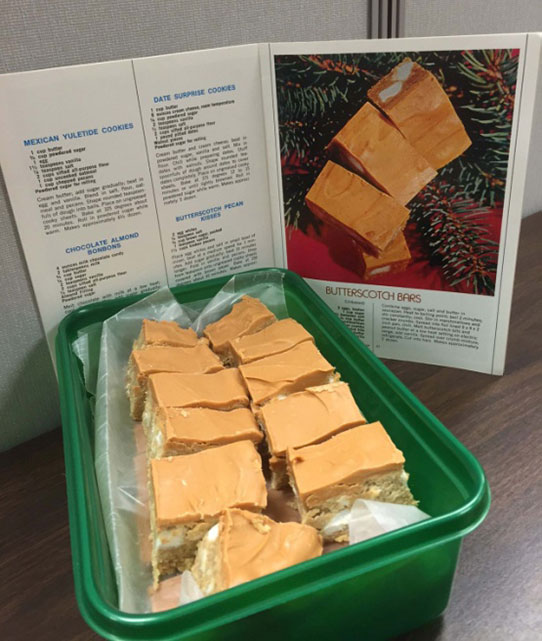

Proof of my commitment to Like-A-Fishhook – Collections Assistant Meagan Schoenfelder made these pop-up models of the site for my birthday last week, based on a ca. 1868 sketch by Maj. Gen. Regis De Trobriand (left) and a map drawn by a former resident, Martin Bear’s Arm, (right).

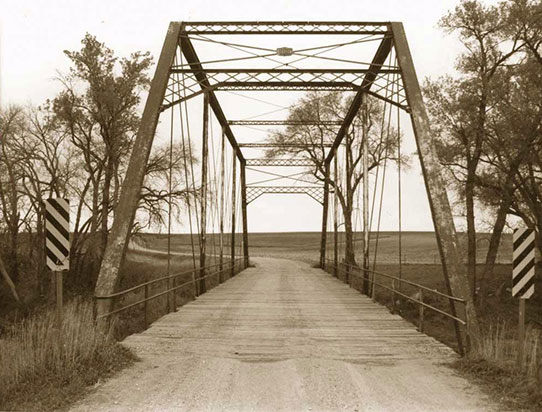

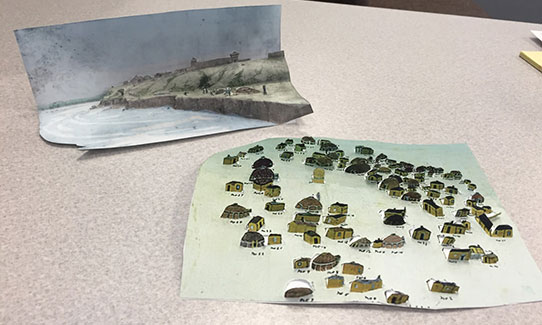

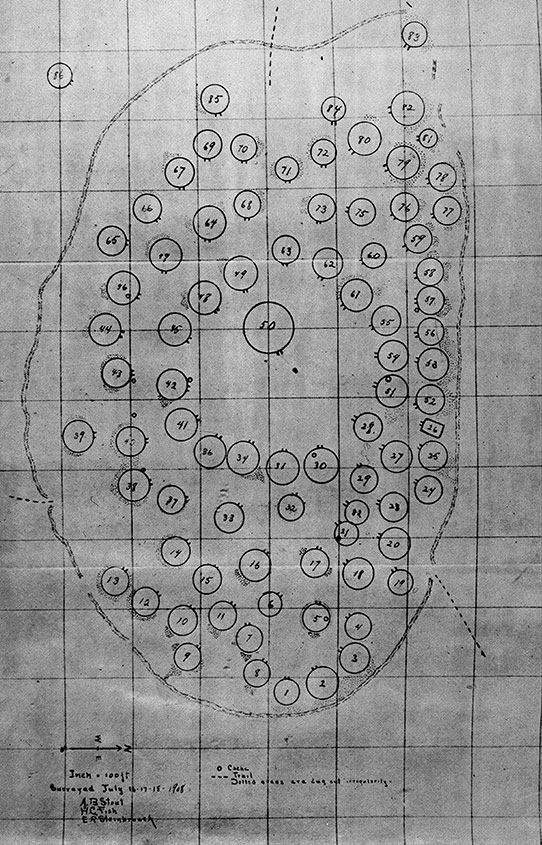

As an alternative to excavation, I am relying on archaeological and historical maps. I thought I should check out the architecture at Star Village, which was built in spring of 1862, across the river from the Mandan-Hidatsa settlement at Fishhook. It was also the site of a battle with the Sioux after that tribe’s dealings with a resident white trader went horribly wrong. The village was burned the same year, and the Arikara moved across the river to Fishhook. Here is the map of Star village, based on surface indications, drawn by A. B. Stout in 1908.

Map copy of Star Village, 1908. (A.B. Stout, H.C. Fish, and E.R. Steinbrueck).

Opening that folder was the best part of my day, because I did not find just maps. I found that Stout had also kept notes on the sites he mapped. For this particular one, he mentioned that he was working with a former resident, an Arikara man named Bull Neck. Bull Neck assisted with the identification of the round earthlodges (drawn as circles on the map), speaking to Stout and SHSND Curator H.C Fish through an interpreter named Alex Sage. Included in these notes are details Bull Neck provided regarding who lived in 22 of the 94 lodges. Bull Neck did happen to mention that the only rectangular building at the site was not a dwelling, but was used by a man named Sun to stable his horses (No.26).

This is the only written documentation I have found indicating this possible use for log cabins. These cabins become much more common in the 1870s at Like-A-Fishhook, and other records indicate that they were used as dwellings as well – understanding this architectural transition from earthlodges to log cabins after European contact is something I plan to investigate with colleagues next year, after my dissertation research is complete (and by the way, I can’t believe how many research ideas I come up with when I am supposed to be focusing on finishing another project).

Some other highlights from the notes, relating to the numbered lodges. Each number corresponds to a lodge on the map:

No. 9 - The residence of the white trader (name unknown), identified by Bull Neck as the origin of the battle leading to the site’s abandonment

No. 30 – Lodge of White Eagle, great grandfather of Alex Sage (the interpreter we used). He held or kept pipe of peace now in possession of Sitting Bear. His wife was Old Woman. This was the lodge of laws and council.

No. 32 – Lodge of White Shield, head man of this village. His wife was Corn Pile.

No. 51 – Lodge of head of all medicine men named Soup. Soup’s father was Holy Bear. Family – a site and adopted child, Bear Goes Out.

No. 54 – Lodge where the bear was represented – everything representing the bear was kept here – bear skin, cloth, etc. No one lived here – put up tent tepee in front for preparation for dance.

No. 83 – This was the first house built in village – was lodge of only Mandan in village his name was Chief. Had wife – one daughter and one son named Long Tail.

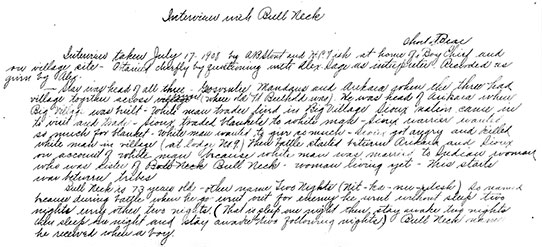

Excerpt of hand-written interview (copy) with Bull Neck, conducted by Stout and Fish on July 17, 1908.

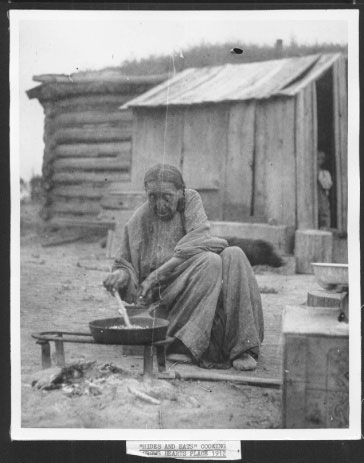

In the interview with Bull Neck, we also learn about his family, as well as the battle that led to the site’s abandonment. As an archaeologist, I am much more accustomed to using data to make generalizations about human behavior. These notes remind me that this “village” was made up of individuals who all had their own relations, memories, and experiences that archaeologists can’t usually capture in their interpretations. What we think of today as abstract “archaeological sites” were once homes – familiar landscapes and communities where people’s lives unfolded in real time.

I know Stout’s passion was plant genetics, but I still need to give him a shout-out for his brief foray into archaeology. This little-known gem in our flat files contributes much to our understanding of Arikara village life.