Adventures in Archaeology Collections: A Tour of the Big Collections Room

In past blog posts, I gave a sneak peek at the initial processing lab and the main archaeology lab. Today, let’s take a tour of the big archaeological collections storage room.

Comparisons have been made to the warehouse at the end of “Raiders of the Lost Ark”—but don’t worry, we have much better finding aids. We want people to be able to find the artifacts in the big archaeological collections storage room and use them for research, exhibits, and educational events.

This room was designed to hold at least 20 years of future incoming collections and related materials, with moveable shelving adding extra storage space. This gives us room to store large, oversized objects not currently on display, like this earthlodge model.

This large model of an unfinished rectangular earthlodge shows how it was constructed.

In this room we keep educational, federal, and state collections as well as accession paperwork and storage supplies.

The archaeological educational collection is one of my favorite collections to show people. You don’t just get to peer at items in this collection from afar—you can touch, hold, and look closely at them.

Some objects in the educational collection are replicas, objects that were made recently but from the same materials people used in the past. Because things like wood, hide, and sinew usually do not last long in North Dakota’s environment, replicas are often the only way to show objects made from these materials. For instance, the wooden paddles that were used to shape pottery.

Replica wooden pottery paddles and pottery sherds from the educational collection.

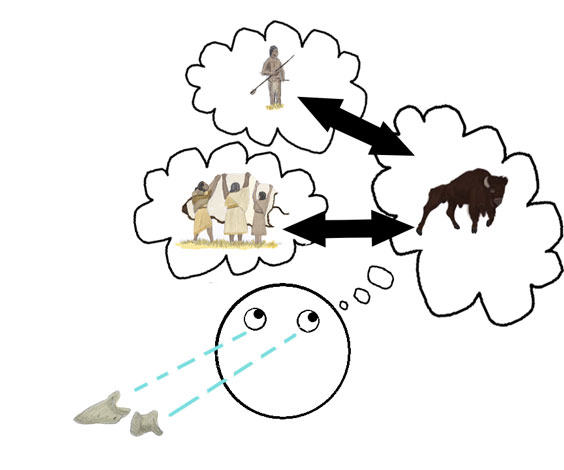

Sometimes replicas are used for experimental archaeology. Experimental archaeology involves using the same kinds of tools used in the past to learn more about how something was done, such as making stone tools. Replicas are often used so the original artifacts are not damaged or destroyed in the process.

A replica flintknapping kit for making stone tools. From left: a leather pad, a stone abrader, a deer antler tine flaker, a hammerstone, and an elk antler billet.

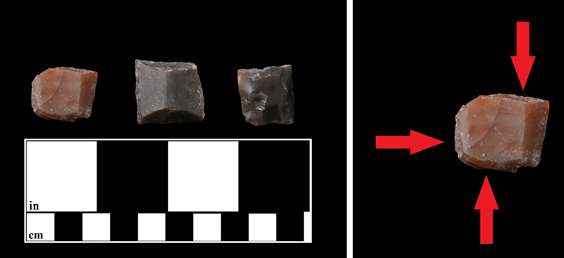

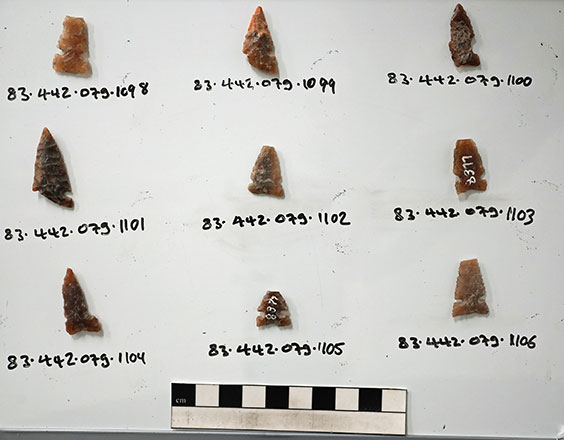

Other objects in the educational collection are cast replicas. Casts are made from a mold or 3D scan of a real artifact. This is useful for artifacts that are too fragile or rare to handle, or for artifacts that come from places outside of North Dakota. Only North Dakota collections are currently accepted into the archaeology collections. But sometimes it is useful for researchers to have access to comparisons from other places. This projectile point is a synthetic cast of a real Paleoindian projectile point from the Mill Iron site in Montana.

A realistic cast replica of a Goshen Paleoindian projectile point from the Mill Iron site in Montana.

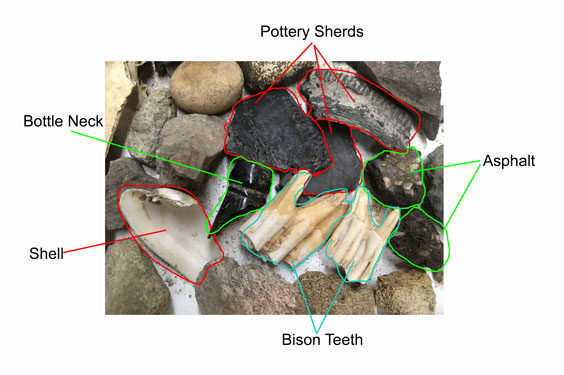

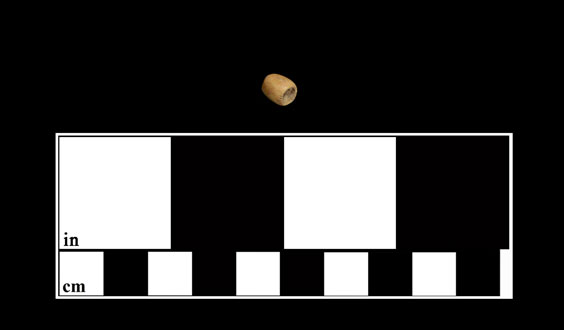

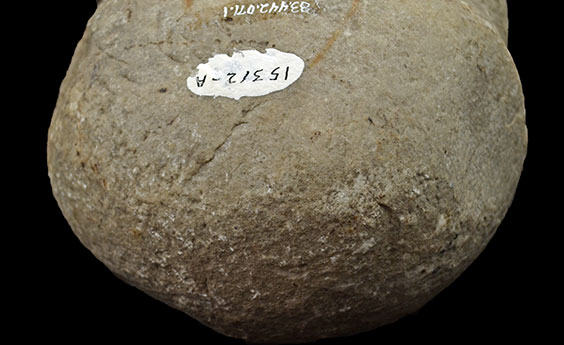

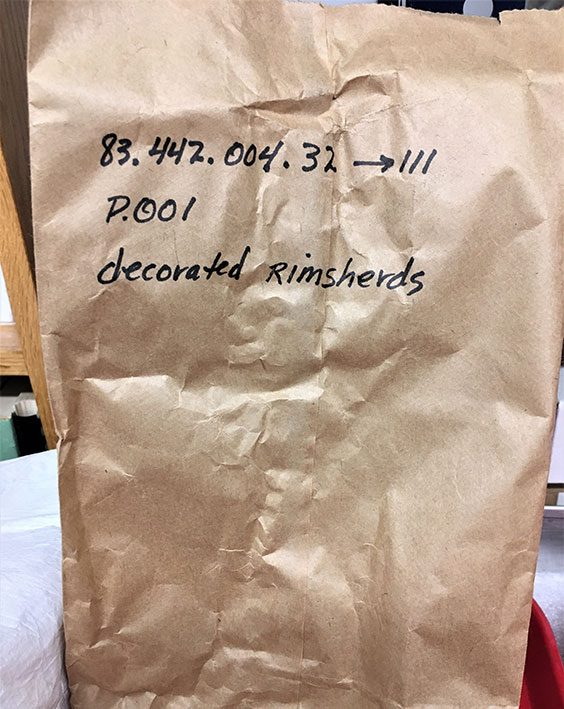

The real artifacts in the educational collection have little or no provenience (i.e., we do not know exactly where they are from or what was found around them). While this means they are not very useful for scientific study, they are still useful for learning about objects and material types. Many of these artifacts are donated.

Examples of real artifacts with low provenience. Even though such artifacts might not be scientifically studied, they are very useful for training volunteers and staff to identify different kinds of materials in collections.

Collections from federal lands in North Dakota are kept in this room. We help curate North Dakota’s federal collections for the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the U.S. Forest Service, and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

This is just part of the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation’s North Dakota collections!

Artifacts from projects on state, county, or municipal lands are also stored here, in addition to donations from private landowners.

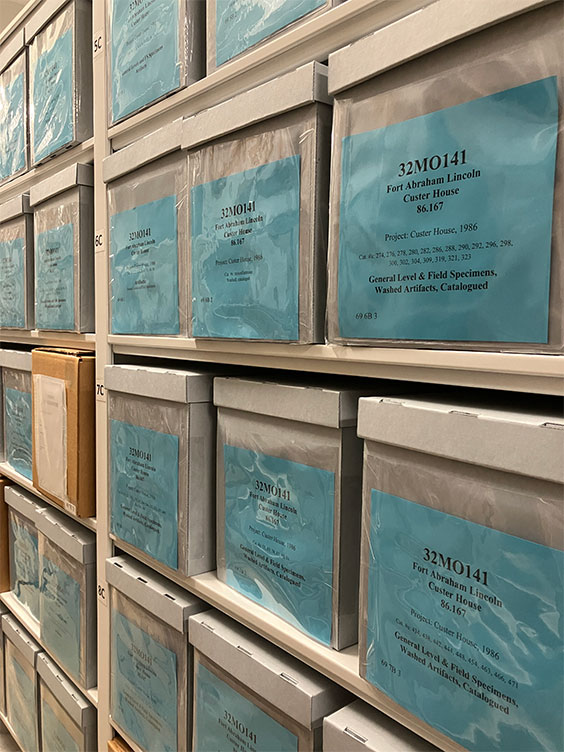

These boxes hold artifacts from Fort Abraham Lincoln (32MO141) and are part of North Dakota’s state collections.

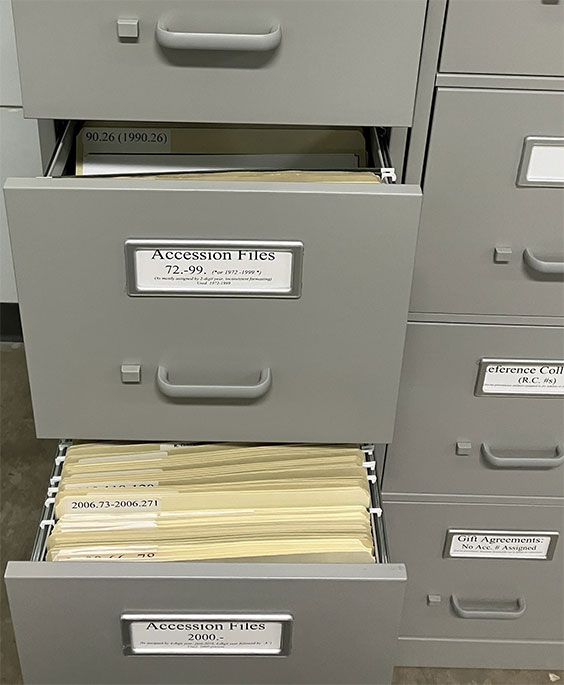

Filing cabinets and storage supplies might not be too exciting to look at, but they are important. These are the accession files. Accession files tell us who donated a collection or what federal agency owns the collection and where the artifacts came from.

These accession files might not look exciting, but they hold treasures of information, such as where collections come from and who donated them.

Storage space for supplies means we can continue moving North Dakota’s collections out of old acidic boxes and into better materials to preserve the artifacts for the future.

Archival boxes ready and waiting to be put to good use.

If you would like to schedule an in-person tour of the archaeology collections, please contact us.