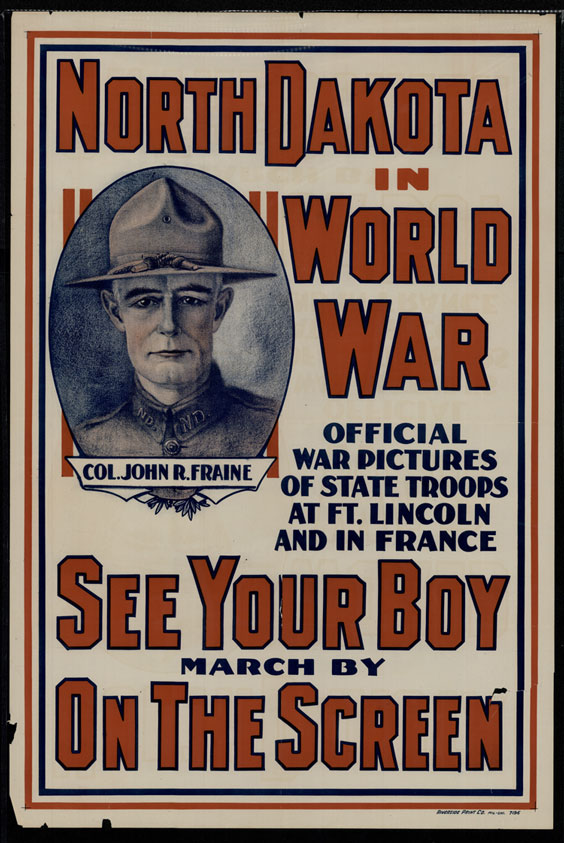

Ice Cream, Accordion Music, and Kite Flying: North Dakota State Historic Sites Offer Summer Visitors a Season of Delights

A new season is upon us, and we are thrilled by the prospect of delighting visitors at our state historic sites. There is much curiosity about what kind of season we will have this year. Last year was tough on sites. Our site supervisors worked hard to open on short notice, create procedures to keep visitors safe, and rearrange schedules to accommodate staff in quarantine. This year we are ready for guests and providing new events and experiences.

As part of their effort to keep visitors safe in 2020, sites canceled many summer events they would typically hold. This year, we have established new guidelines for events at sites, and I am super excited about the great events we will be hosting. Some are returning favorites; others are brand new. There are too many to list each one, but here are a few highlights of what’s happening at sites this summer:

June 27 Great Western Trail Monument Dedication. Missouri-Yellowstone Confluence Interpretive Center, near Williston

July 3-4 Kite Flying Weekend, 9 a.m.-4 p.m. Fort Abercrombie State Historic Site, near Fargo

June 15 and July 13 Entertainer Kittyko holds a child-oriented performance, 11 a.m.-12 p.m. Former Governors’ Mansion State Historic Site, Bismarck

July 24 Grant Invie Concert. 1883 Stutsman County Courthouse State Historic Site, Jamestown

August 8 Annual Ice Cream Social returns. Former Governors’ Mansion State Historic Site, Bismarck

August 14 Painting class with Linda Roech. Welk Homestead State Historic Site, near Strasburg

August 17 Entertainer Kittyko holds a child-oriented performance, 11 a.m.-12 p.m. Camp Hancock State Historic Site, Bismarck

The annual ice cream social at the Former Governors’ Mansion State Historic Site returns this summer after a pandemic-related hiatus.

Beyond events, some sites will also offer new experiences for visitors this year. Fresh off of their success opening Fashion & Function: North Dakota Style, the exhibit team has been hard at work on a new Sitting Bull exhibit for the Missouri-Yellowstone Confluence Interpretive Center (MYCIC). The exhibition focuses on the Hunkpapa Lakota leader’s life and cultural impact and will open in June. Last year we installed a new civics exhibit at the 1883 Stutsman County Courthouse State Historic Site. With the looming threat of COVID-19, many of the hands-on elements in that exhibit had to be put on hold. This year, however, thanks to some new procedures and the improving pandemic situation, we are now able to bring these elements to the public.

Visitors to the new civics exhibit at the 1883 Stutsman County Courthouse State Historic Site will finally be able to try their hand at the embossing stamp shown above. This stamp was one of several interactive elements put on hold due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Meanwhile, at the Ronald Reagan Minuteman Missile State Historic Site, Rob Branting, site supervisor, will conduct a new interpretive tour of November-33. (November-33 is a decommissioned Launch Facility, which housed a Minuteman III missile that could be fired from a Launch Control Facility such as Oscar-Zero.) Rob’s tours will take place on alternating Fridays and Saturdays in the summer from 11 a.m. to 2 p.m. Contact the site for details.

At the time of this writing, some site projects and programs are still works in progress. At Camp Hancock State Historic Site, our Site Supervisor Johnathan Campbell is working to recreate how U.S. Weather Bureau offices once located at the site would have looked in the 1930s. Similar to the civics exhibit at the 1883 Stutsman County Courthouse, the recreated Weather Bureau offices will incorporate hands-on elements. The Ronald Reagan missile site is planning a Perseid Meteor Shower Party for the evening of August 12. The 1883 Stutsman County Courthouse will host talks by both the veterans officer for Stutsman County and the president of the county commission. The Welk Homestead State Historic Site is organizing its annual Accordion Jam Festival, slated for July 17. At the Chateau de Morès State Historic Site, staff are collaborating with the Friends of the Chateau de Morès to convene a series of outdoor painting classes with Joseph Garcia, site supervisor at MYCIC and Fort Buford State Historic Site.

If these or other events mentioned in this blog sound of interest, keep an eye on the site’s Facebook page for further details, or check out the events page on the State Historical Society of North Dakota’s website.

Couples polka during the 2019 Accordion Jam Festival at the Welk Homestead State Historic Site.