Hunting “Easter Eggs”: Small Details in Historical Photos Add to Interpretation

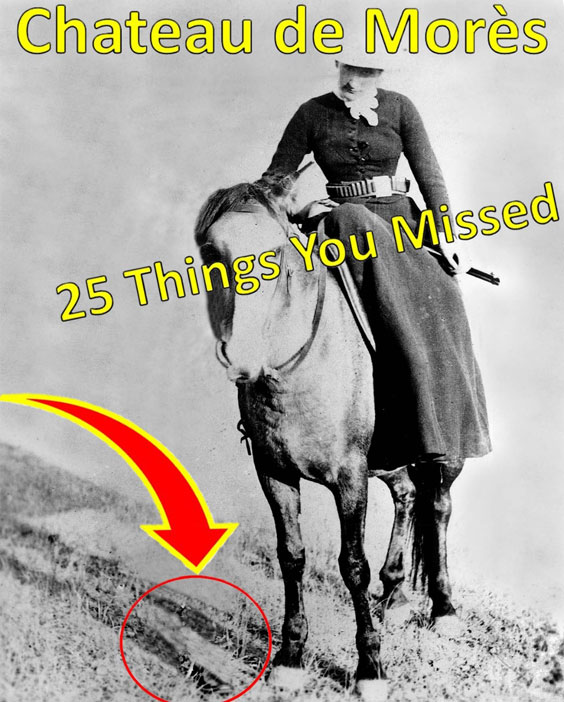

It is not uncommon for film directors and video game designers to put Easter eggs into their movies and games. No, I am not talking about literal Easter eggs, but rather hidden references to other films or aspects of pop culture—for instance, the alien from “E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial” appeared in “Star Wars: Episode I-The Phantom Menace.” Some people actively hunt these hidden treasures. You can often find videos on YouTube with a clickbait image that claims to reveal all the Easter eggs in a given movie. These videos usually have a screenshot from the film with a red circle around some aspect of the background and a title that reads “25 things you missed.” Historical photos can also have Easter eggs, although these are not intentional. These details can change how we view the image and give us a better context for telling these stories. Here are some I found while working on interpretive panels for Chimney Park at the Chateau de Morès State Historic Site in Medora.

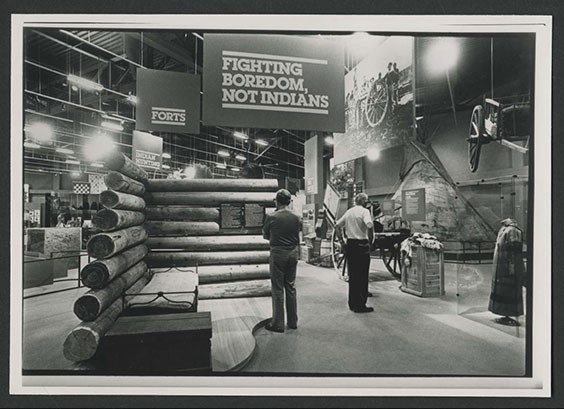

Here I have inserted my own clickbait thumbnail like you might find on YouTube. There really is more to this photo than meets the eye. For instance, the Marquis de Morès was photoshopped out of the image. Look closely and you can still see the toe of his boot and shadow. The horse is even missing an ear. Since the photo was altered, the image was removed from our digital collections.

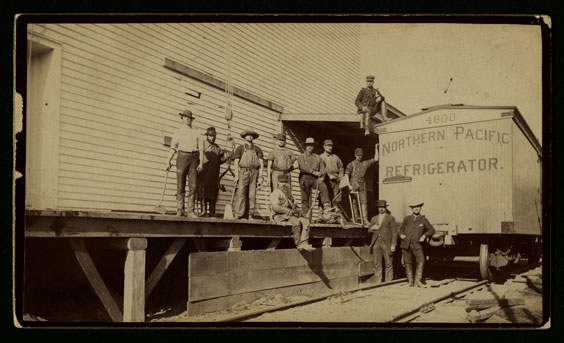

One of the interpretive themes at the Chateau is the Marquis de Morès’ dream of creating a cattle empire. Staff at the historic site talk about his desire to change the system for transporting beef from shipping live cattle to slaughterhouses in Chicago to shipping dressed beeves (the flesh of a cow or bull) to East Coast markets using refrigeration. While his was not the first enterprise to use refrigerated rail cars to transport dressed beeves, the scale of the Marquis’ plans were unprecedented.

A closer look at this image reveals the Marquis’ big dreams for his shipping operation. SHSND SA 00042-00188

The 1883 photo above shows the construction of the Marquis’ abattoir (slaughterhouse). We can see the main structure, with its icehouse under construction. A spur line runs between the two structures, bearing four of the Marquis’ new refrigerated rail cars. It is easy to focus on the construction and miss what, in my opinion, is the most crucial part of the photo. I know I did.

If you zoom in on a high-resolution scan of the photo, as I have below, you can read the words on the side of the rail cars. They are still a bit difficult to make out, but the places they plan to deliver to are listed, from to Duluth, Minnesota, to the West Coast, as well as the products they plan to deliver, including beef, beer, and vegetables. (You can view the full list of items and places advertised on these rail cars at the detail page here.)

Fresh meat, butter, fish, and beer were among the perishable products the Marquis planned to ship on his refrigerated rail cars. SHSND SA 00042-00188

Why is this important? It shows just how big the Marquis dreamed. He had not even finished building all the infrastructure his company needed and already was listing places he would deliver to and goods he would carry. It would be like listing all the stores that will carry your new product before finishing the factory. We know now that the Marquis would not actually accomplish most of this vision, but it does show his ambition, confidence, and the sheer size of his dream. It also shapes how we at the State Historical Society share that story with visitors.

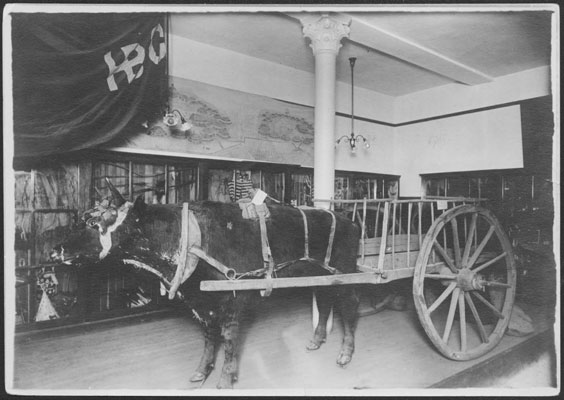

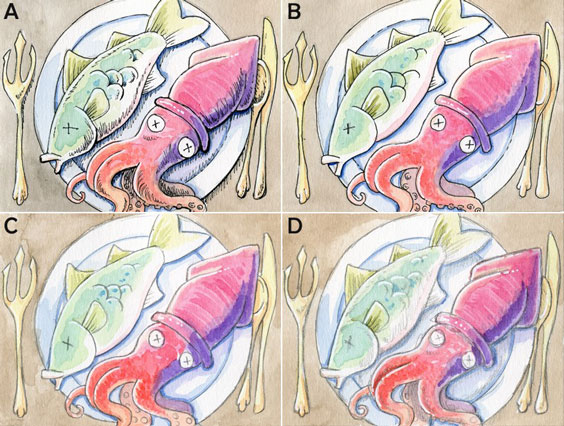

During my research, I’ve also discovered that the public at the time was fascinated with the meatpacking industry. A dark, macabre sense of humor was often displayed by the workers and companies involved in these processes. Armour & Co. produced a postcard featuring a hog wheel (used to lift live hogs to the conveyor belt system) with the slogan: “Round goes the wheel to the music of the squeal.” The Marquis’ abattoir was not immune to this dark humor, and the Easter egg proves that point. Take a close look at this photo below. What do you see?

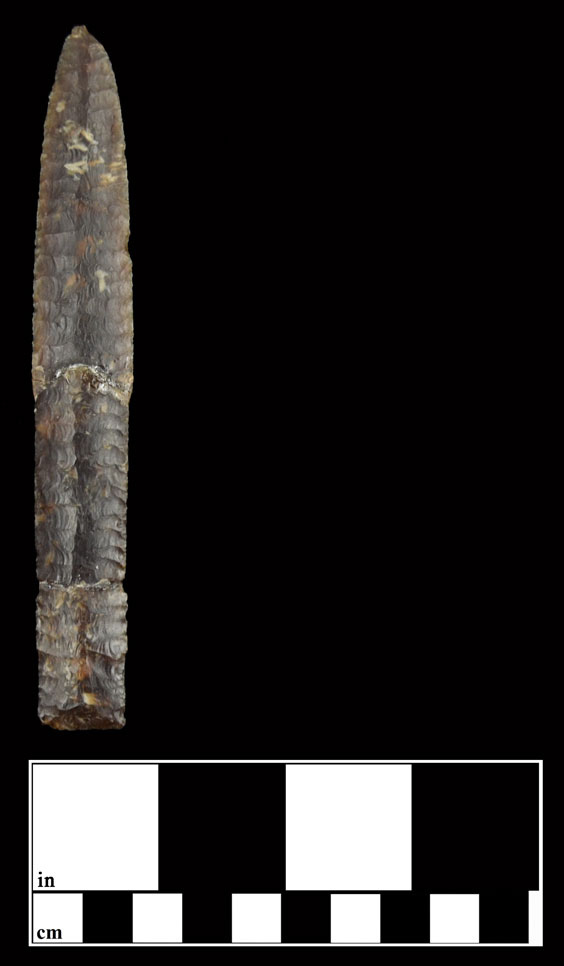

Another interesting tidbit in this image is the pistol hanging from the belt of one of the men. I will need to further investigate. SHSND SA 00042-00150

Most people will say they see a group of workers holding tools posed on the abattoir’s loading dock. But look closer, and you can spot one man resting his foot on the decapitated head of a butchered cow as if he was a big game hunter.

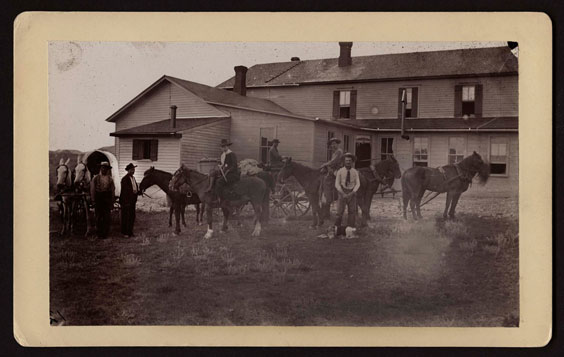

Finally, I want to share one of my favorite Chateau Easter eggs. The worst position for a servant at the Chateau was to be the chambermaid. The Marquis and Marquise had exclusive use of the one indoor bathroom at the Chateau. Servants and guests used chamber pots, and the chambermaid was responsible for cleaning these every day. It would be inefficient for her to carry each pot downstairs to dispose of the contents. Instead, the chambermaid would empty the contents into a bucket. The chambermaid would not want to keep a bucket of foul-smelling waste sitting where it could affect the guest quarters’ air quality while she finished cleaning the 10 upstairs bedrooms. So, she would place the bucket outside a window on the roof until she needed it for the next pot. Knowing that, take a look at this iconic photo below of the Marquis, the Marquise, and their hunting party ready to go out on a hunt.

Getting ready for a big hunt at the Chateau de Morès, circa mid-1880s. SHSND SA 00042-00191

Can you spot it?

I recommend taking some time to explore the images on Photobook. Who knows what Easter eggs you might find? Happy hunting.